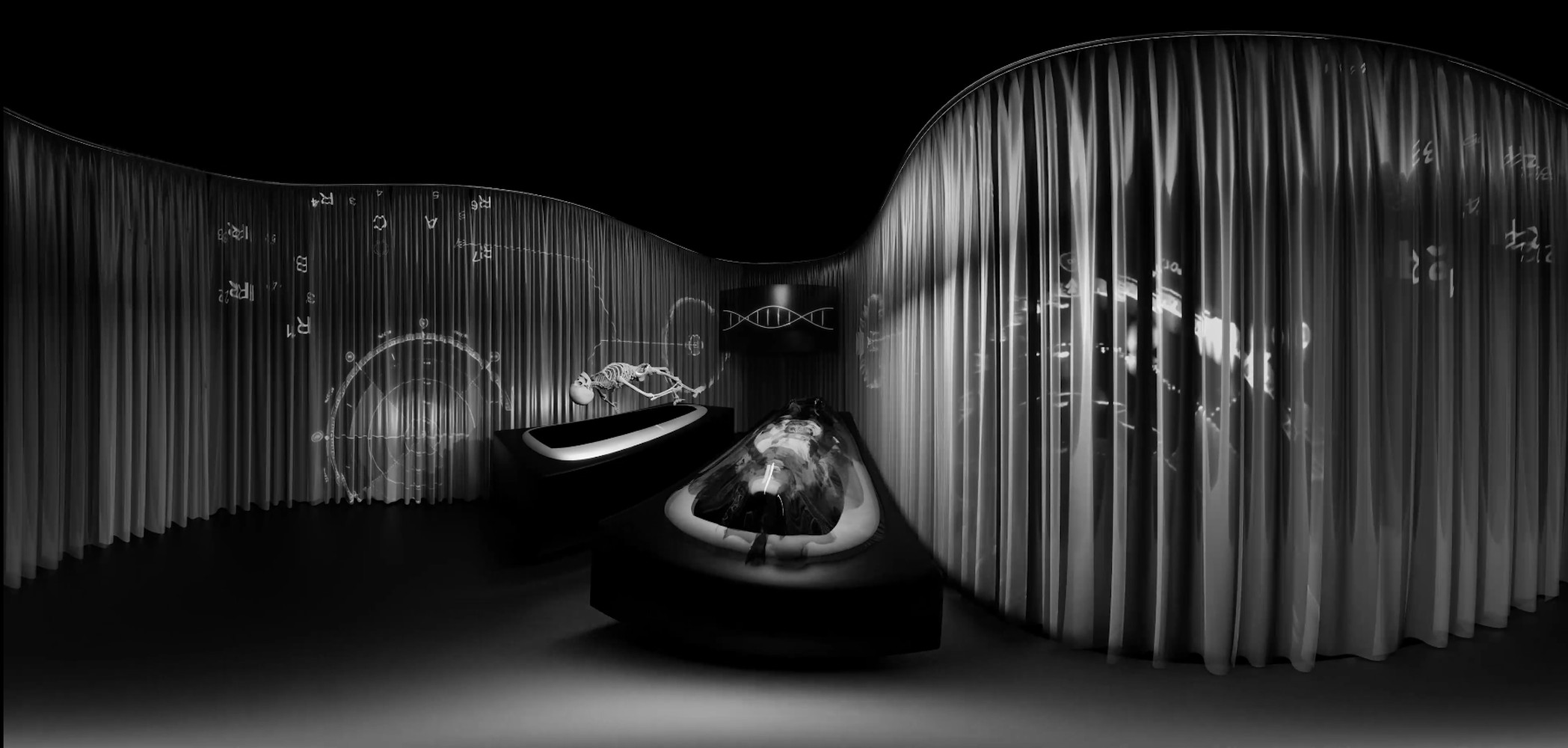

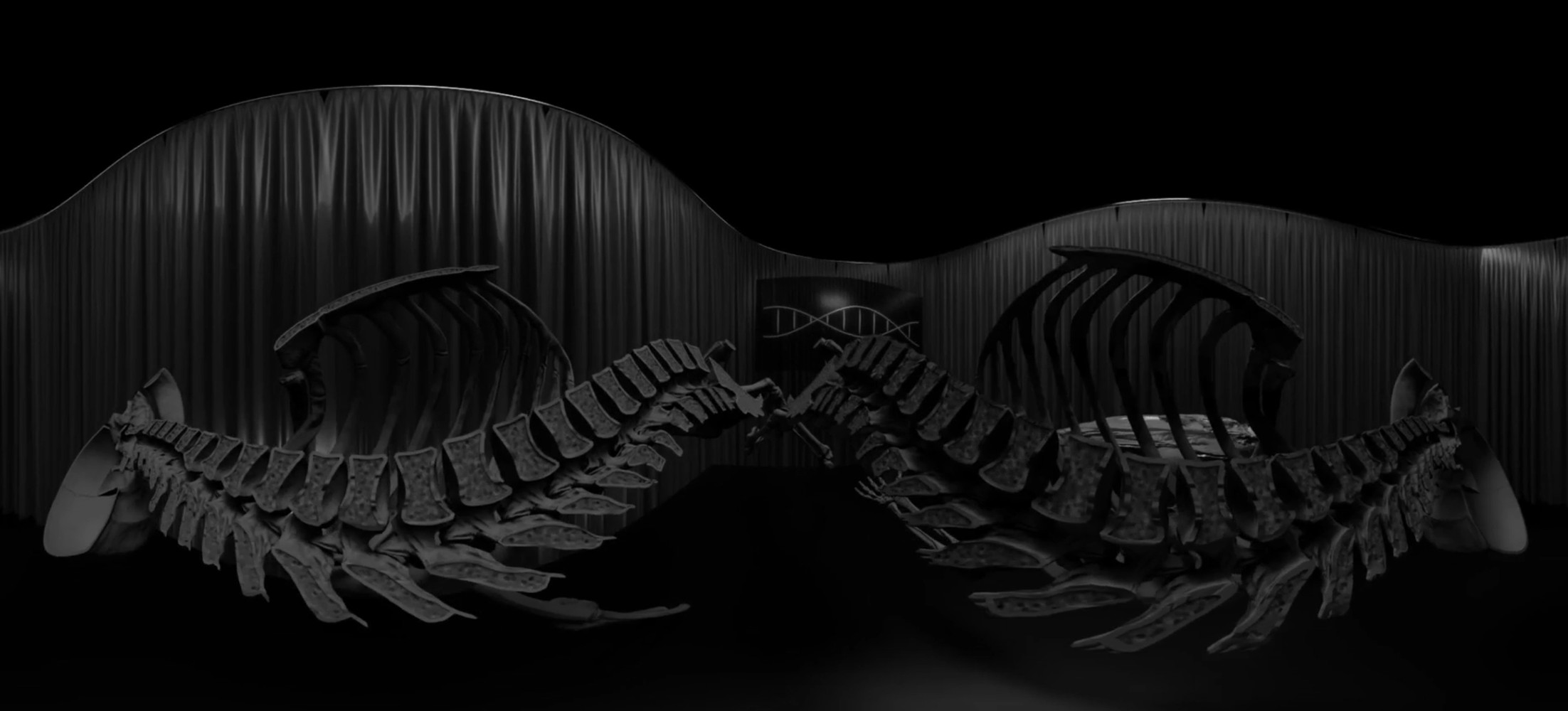

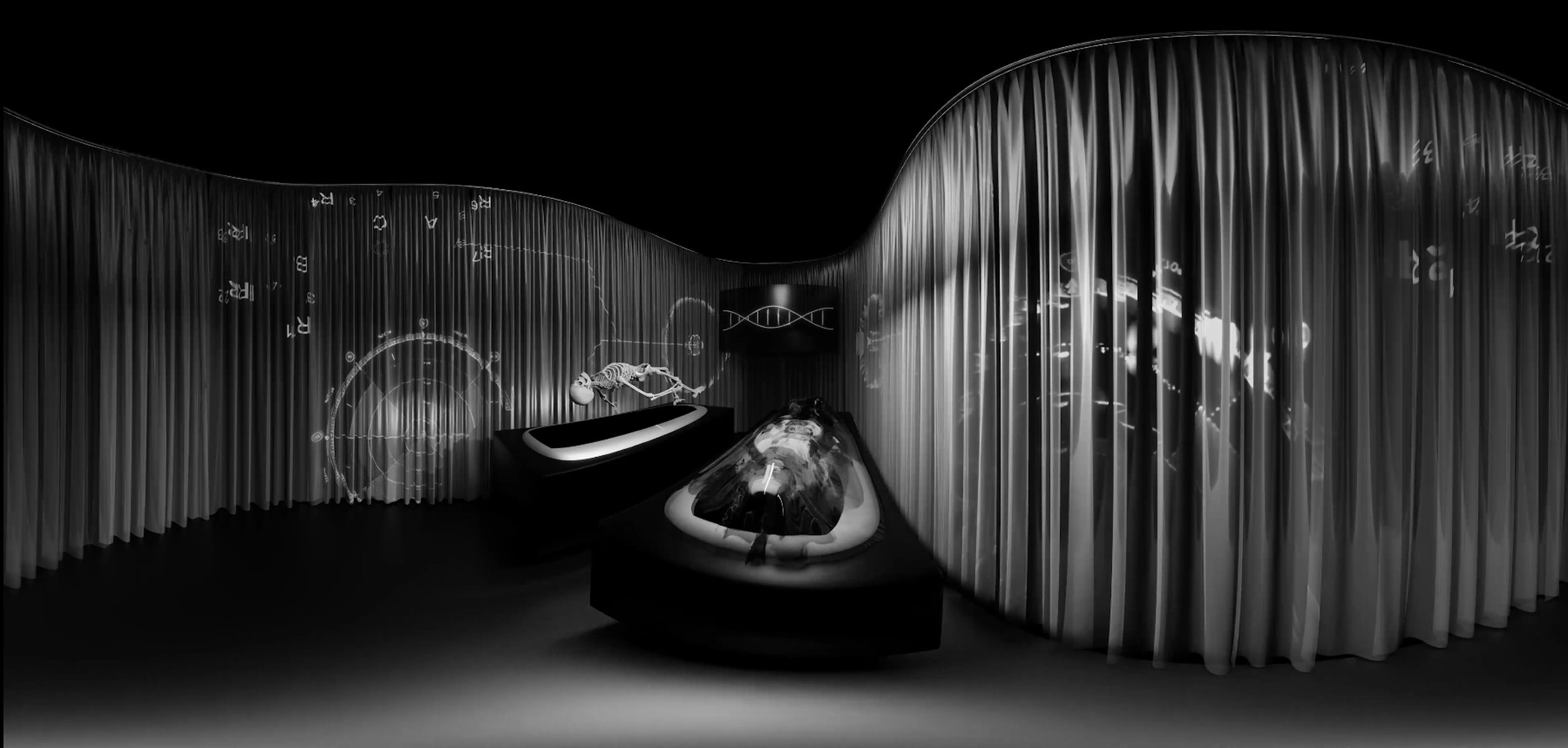

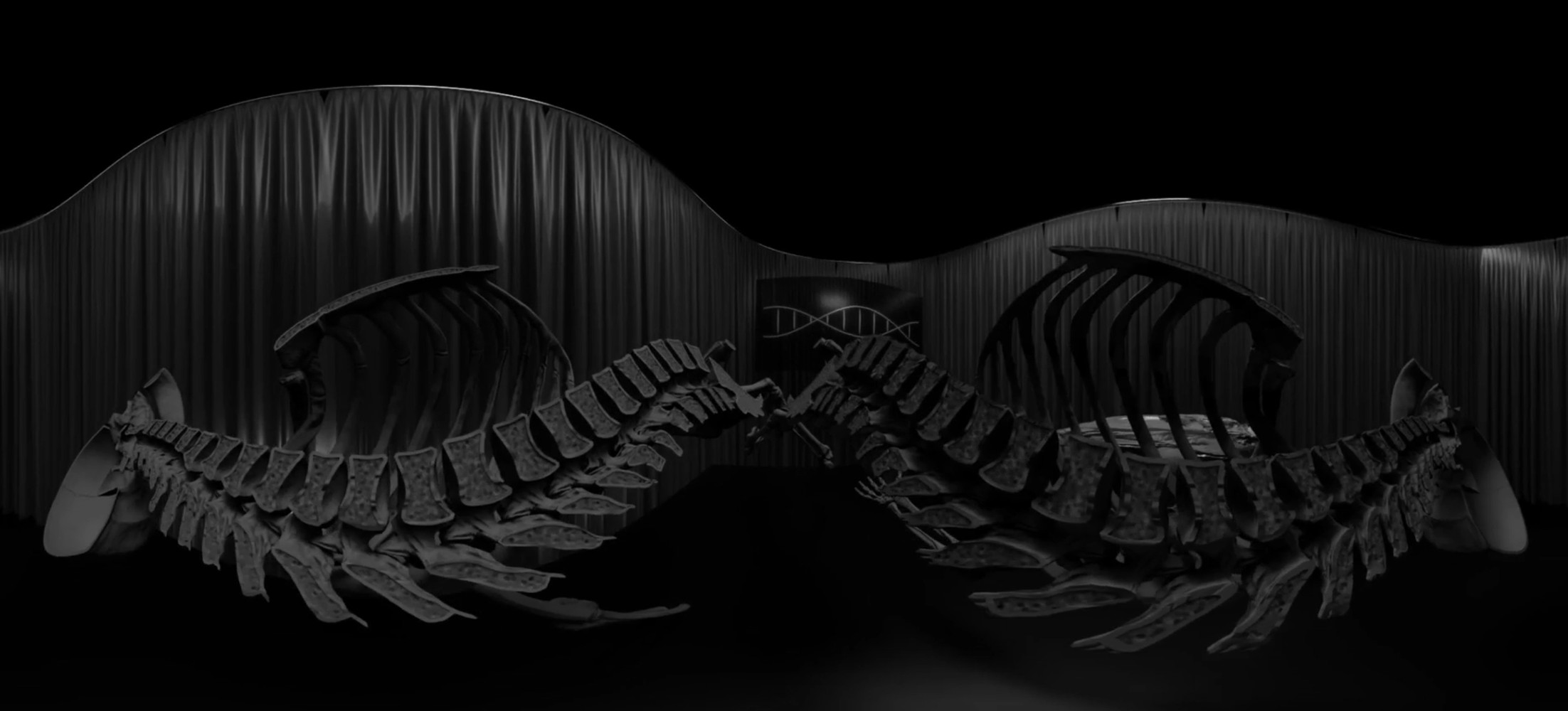

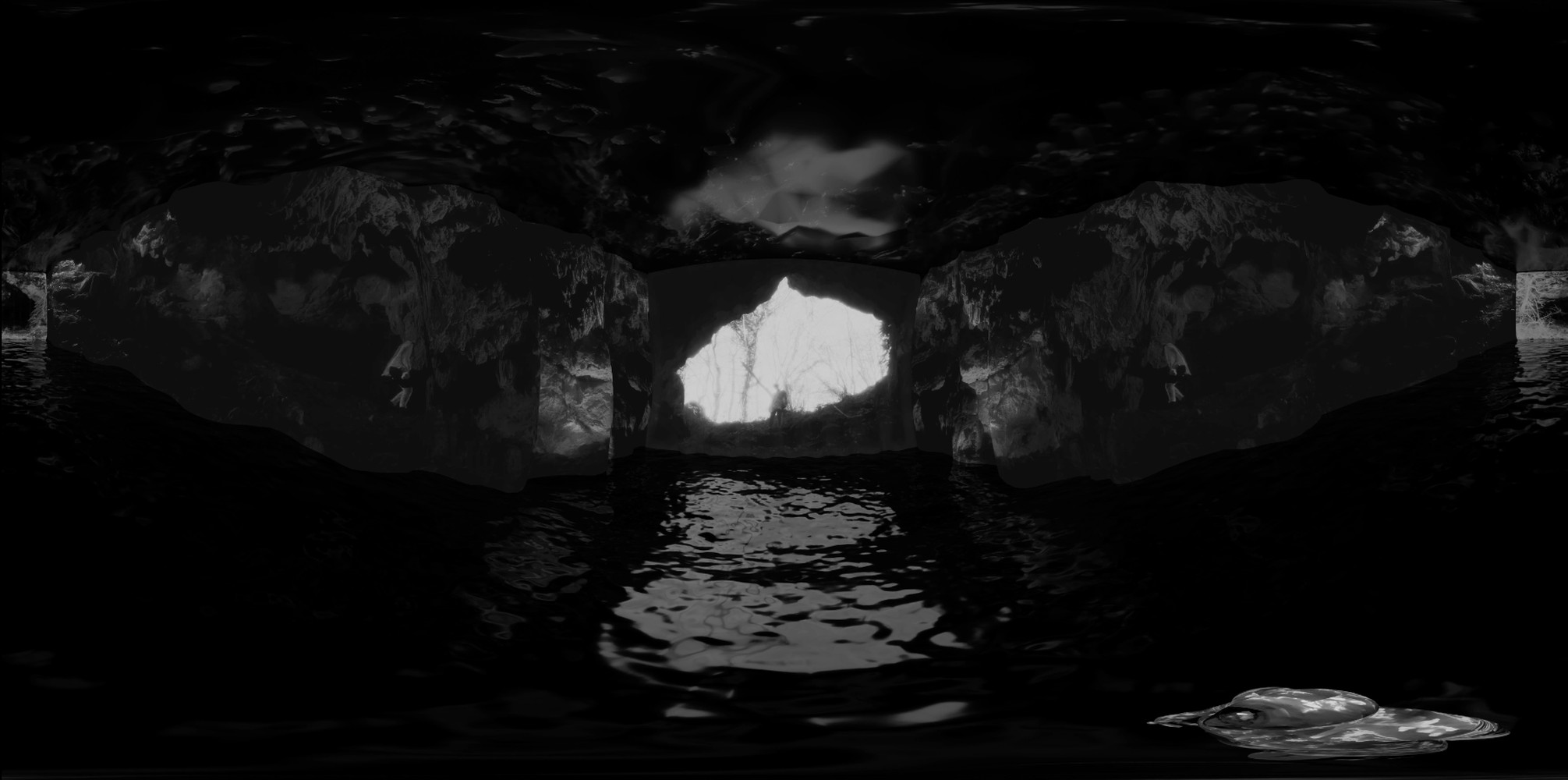

Installation textile immersive VR 360 stéréoscopique. (16’) / Immersive textile installation VR 360 stereoscopic. (16’)

« Some we know to be dead even though they walk among us; some are not yet born though they go through all the forms of life; other are hundreds of years old though they call themselves thirty-six» Virginia Woolf, Orlando, 1928

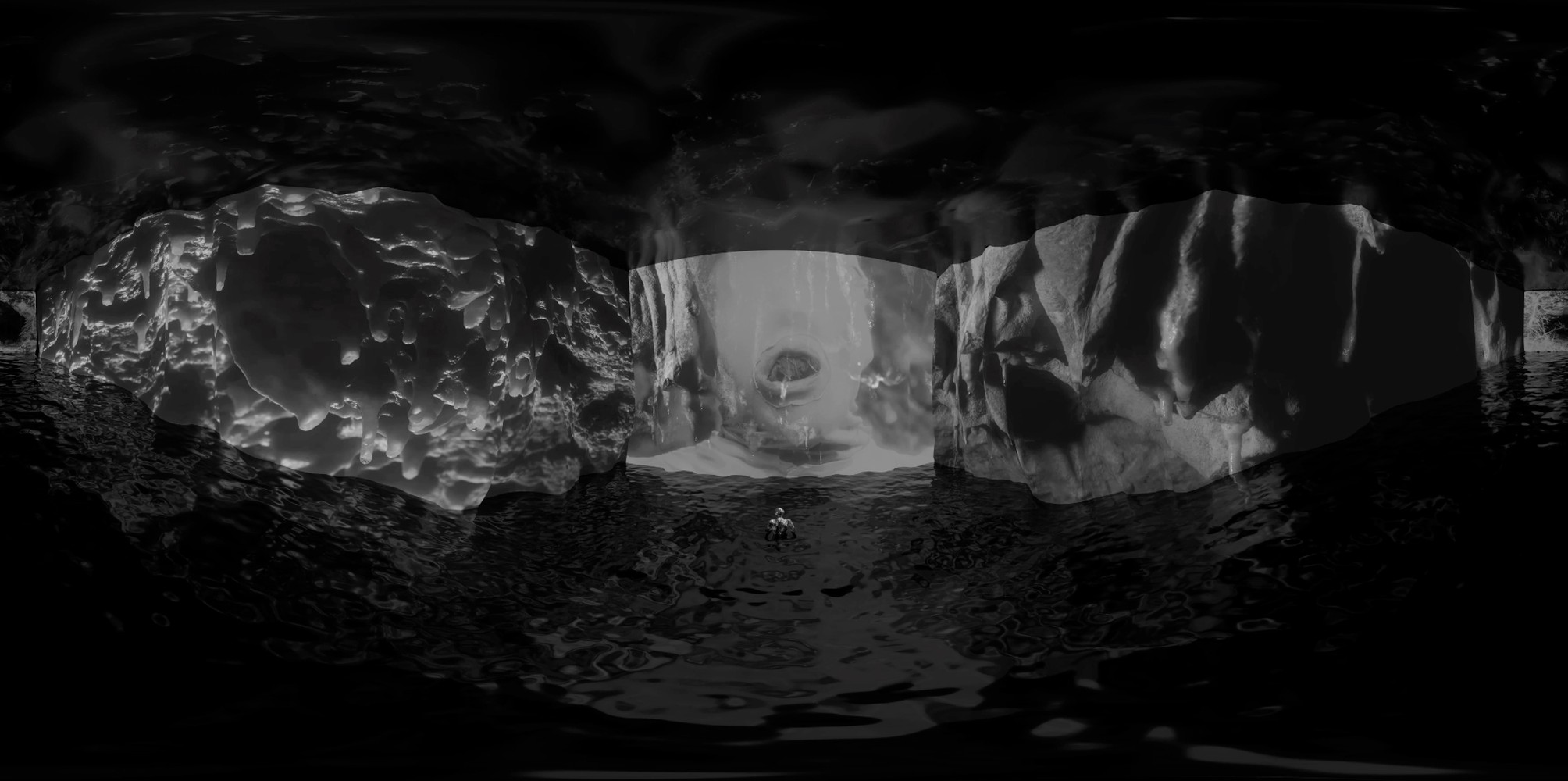

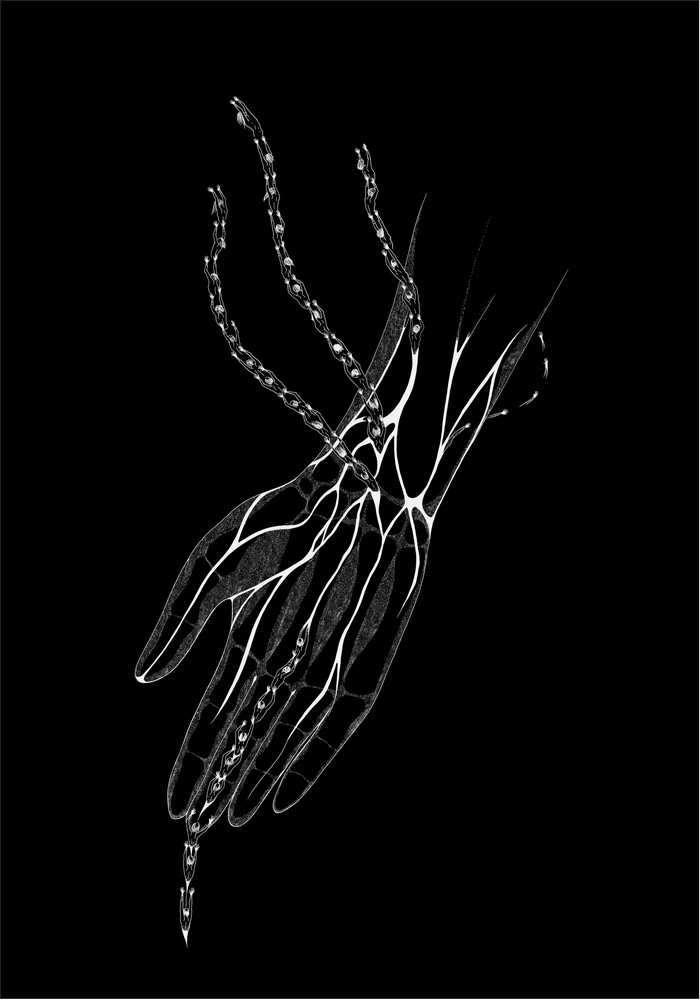

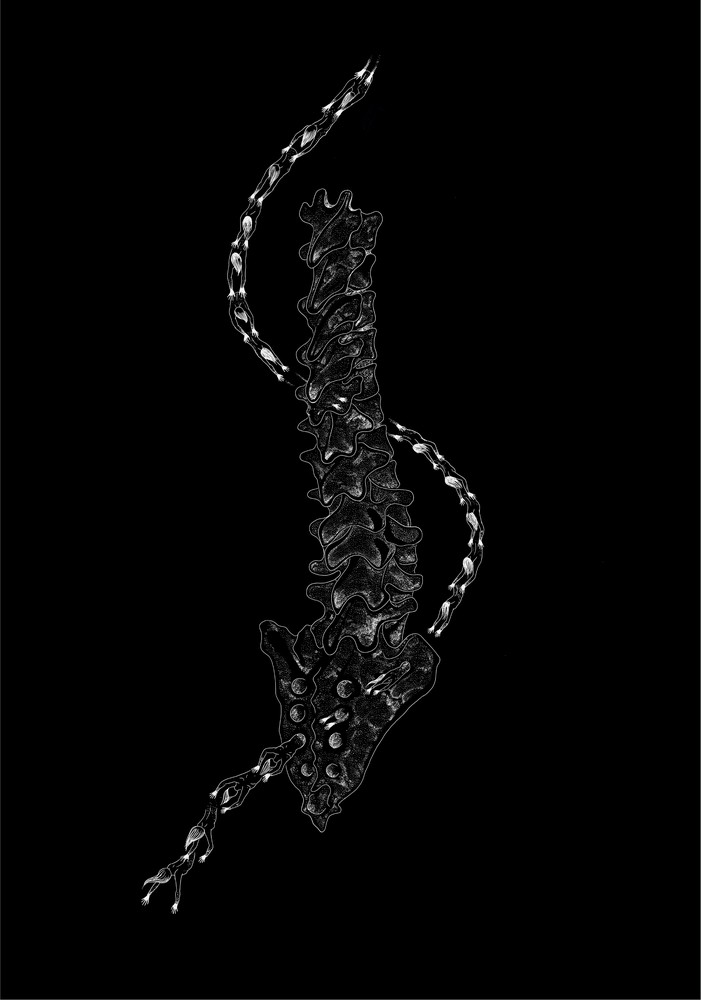

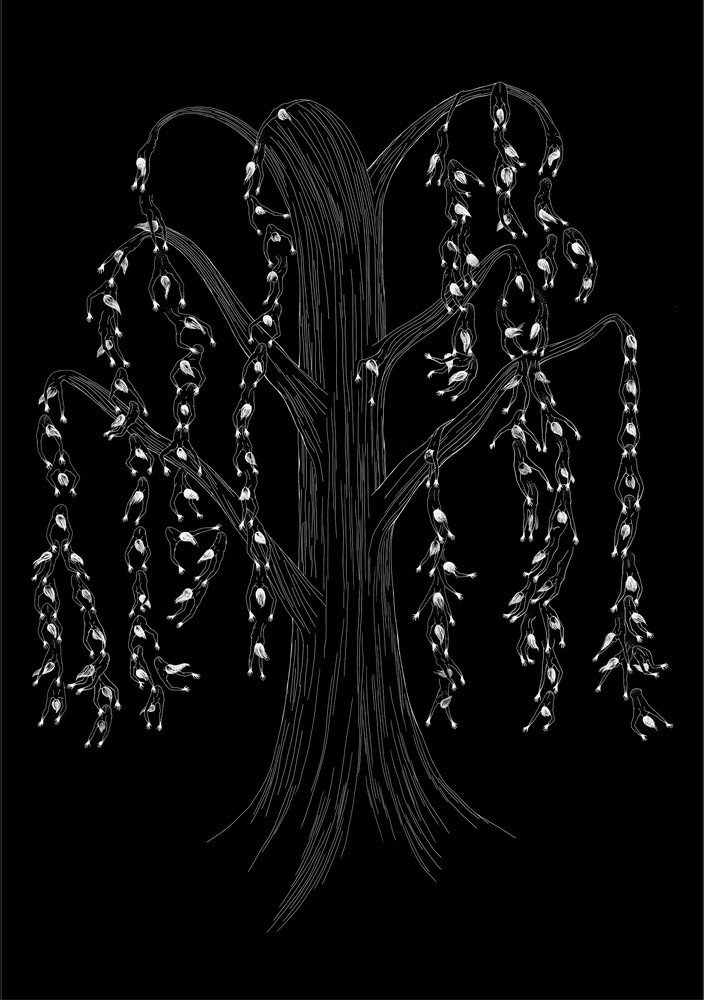

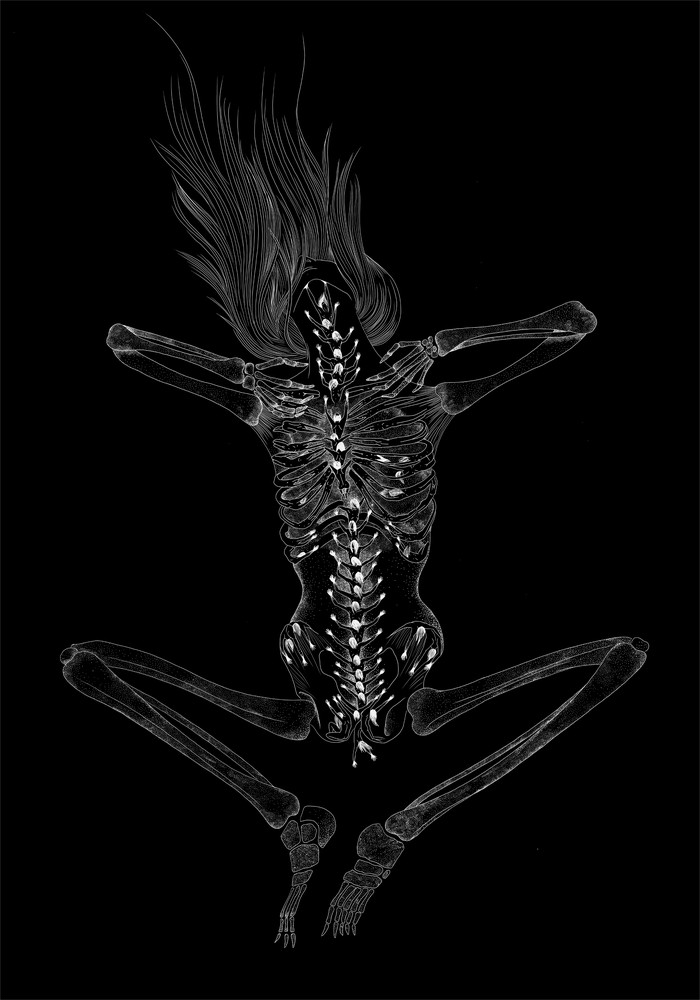

They Dream in My Bones est une installation-fiction racontant l'histoire de Roderick Norman, chercheur en onirogénétique la science qu'il a fondé et qui permet d'extraire les rêves d’un squelette inconnu. Plongé dans l'espace mental de R. Norman, reconstitué sous la forme d'une installation textile composée de dessins et de peintures, le spectateur est invité à visionner un film immersif en 360° stéréoscopique. Conçu comme une fable scientifique minimale en noir et blanc, ce film VR mêlant images de synthèse et images filmiques traditionnelles nous transporte sur des voiles virtuels poursuivre la métamorphose d’un squelette à la frontière de l'humain et des genres.

Dreams.

They dream in my bones. They dream in your bones. They dream in our bones. There are visions, engraved in me, fossilized, petrified. They never stop dreaming. Death can’t stop the visions.

How many dreams are there in me? How many genders are there in me? I used to be a man and a woman, before being born. I used to be a pikaïa, a bactery. So, how many species are there in me?

Merci à tous les supers humain.e.s du Fresnoy, de l'Ariège et d'ailleurs qui m’ont aidée et soutenue dans ce projet, merci aux araignées, au platane et à la grotte, à Ludovic De Oliveira, Cindy Coutant, Alice Goudon, Lilou-Magali Robert, Julian Eggerickx, Les Foudres !, Medhi Formisano, Stéphane Grandin, Kendra McLaughin, Olivier Jonvaux, Santiago Bonilla, Olivier Pasquet, Emanuele Coccia, Bertrand Mandico, Philippe Quesne et Laurent Guido mon directeur de thèse.

Artiste-réalisatrice-chercheuse, Faye Formisano vit et travaille entre Paris et Lille. Insemnopedy I: The Dream of Victor F. (23’), fiction/expérimental (Panorama 21, commissaire : Jean-Hubert Martin ; sélection internationale Étrange Festival 2019 ; les Utopiales 2019 ; Festival international de Munich 2020), produit par Le Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains. Draper l’image : usages et fonctions du voile comme manifestation des identités troubles dans le cinéma fantastique, doctorat de création à l’université de Lille 3 (C.E.A.C de Lille) et au Fresnoy, dirigé par Laurent Guido et co-encadré par le réalisateur Bertrand Mandico.

Née en France en 1984, Faye Formisano met en scène des figures à la frontière du fantôme et du fantasme évoluant dans un monde surréel hanté par le lien défait entre l’humain et son milieu. Issue d’une formation en design textile, elle collabore avec des maisons de couture et des chorégraphes, monte deux spectacles vivants et plusieurs vidéos-danses avant de réaliser son premier court-métrage de fiction au Fresnoy.

Artiste visuelle, chorégraphe et vidéaste issue du design textile née en 1984, je vis et travaille à Paris. Diplômée d’un DSAA de l’école Duperré en 2007, j’y ai entamé une recherche transversale autour du vêtement à danser mêlant la danse contemporaine, la photographie et la vidéo. J’ai mis en scène deux spectacles vivants autour de dispositifs textiles activant de la chorégraphie ( Beach noise, El Grito de la montana) et un rituel performatif et sonore The Rip on my Tongue en collaboration avec le pianiste Benoît Delbelcq. J’ai également réalisé plusieurs vidéo-danses et un film expérimental autour du geste et du son de la déchirure. Les thématiques qui m’habitent sont le lien défait, le temps, la perte, la mémoire et les fantômes. En parallèle, j’ai collaboré avec des chorégraphes comme Mylène Benoît pour des scènes nationales, l’artiste visuel Melik Ohanian et je n’ai cessé de travailler en tant que designer textile, graphiste et peintre sur soie dans le monde du prêt à porter et de la haute couture. Au Fresnoy je souhaite pousser et affirmer mes recherches dans le champs du film expérimental et de l’installation intéractive en questionnant les nouvelles technologies de l’image et les surfaces textiles innovantes et actives.

Il arrive que, quelles que soient les atteintes, un corps ne meurt jamais. Il répond à ce qui le blesse, le met en danger, par un surcroît de présence. Sa disparition ne le rend-elle pas, au contraire, plus vivant ? Dès lors qu’il n’est plus, nous ne cessons de le chercher. le corps bouge avant et après la mort. Il n’y a pas de corps sans cela et de cela, le rêve nous instruit. Plus il est menacé d’oubli ou de destruction, plus nous puisons, dans les forces durêve, un élan qui le métamorphose et le rétablit. Dans la période que nous vivons, où le corps est sur la sellette, où nous est annoncé son évitement, ses évanouissements, sa dématérialisation, le rêve et l’utopie ne cessent de nous rappeler qu’il est toujours sur scène et pour longtemps...

Sur scène ou plutôt sur une des scènes multiples où il passe de l’une à l’autre. Jamais immobile, appelant le mouvement, la danse comme une respiration relançant les battements du cœur.

Par cette impulsion, il s’impose au centre, mais étrangement cette course, par sa vitesse, l’efface en le manifestant, par sa seule lumière qui nous éblouit. Par cette situation, le corps doute de lui-même. Il apparaît, il se dessine dans l’espace, mais l’intensité des lueurs n’est pas son alliée.

Elle le met en question. Il lutte contre une ombre qui le menace et dans laquelle il ne se reconnaît pas. S’il s’identifie d’abord aux lignes qui le cernent, qui lui permettent d’exister, de dire « je », le monde, joueur des multitudes lumineuses, le trouble et le défait. S’il est celui qui vient, il est aussi celui qui fuit. D’abord tache sur la terre, il se liquéfie dans une dilatation ou s’évapore dans une expansion dont nous perdons les confins. notre corps se disperse, se dissémine, et nous serions naïfs de croire en ses définitions physiques ou lexicales. Un temps, il est une évidence, mais celle-ci laisse place à l’inconnu où le salut se trouve dans l’occultation des apparences. Il se réfugie en un « noir » qui envahit l’espace et le recouvre, ayant pour vêtement les ténèbres de la nuit jusqu’à ce que l’éclairement, nécessaire à toute vie, relance la quête d’un être insaisissable, à travers l’image qui renaît.

À ce sujet, Junichiro tanizaki nous pose cette question : « avez-vous jamais, vous qui me lisez, vu la couleur des ténèbres à la lueur d’une flamme ? Elles sont faites d’une autre matière que celle des ténèbres de la nuit sur une route et, si je puis risquer une comparaison, elles paraissent faites de corpuscules comme d’une cendre ténue, dont chaque parcelle resplendirait de toutes les couleurs de l’arc-en-ciel. »au contact des œuvres de Panorama 23, j’éprouve cette sensation d’un territoire composite de cendres retournées par l’art en une suite de couleurs, réfractées dans l’eau et la lumière.

Répondre au délitement du monde par la danse, l’explosion bigarrée, traverser et spéculer avec ce qui l’éclaire ou l’efface, du noir au blanc, n’est pas une affaire de solitude. Éprouver la variabilité de ce va-et-vient, de cette métaphore, implique l’altérité, réclame l’autre qui invite au changement, à la fusion de substances différentes.

Cet autre est présent de façon insistante dans ce Panorama 23, il est la source et le flux du courant qui lie les œuvres. S’avancer par les chemins de l’exposition, c’est plonger dans un univers dont le principe est le croisement, le mélange, l’abouchement, comme il en est dans les mouvements de la mer, dans ses fonds marins. les créateurs réunis ici questionnent le corps et le langage, ils m’évoquent l’introduction de Moby Dick où Herman Melville définit son héros comme un nageur debibliothèque. oui, il s’agit bien de plongeurs qui nous emportent dans des flux qui sont la nature du monde où les corps se baignent, jusqu’à devenir le flux lui-même, cherchant à se fondre avec le corps de l’autre. Ils rêvent d’un corps possible où le morcellement, la coupure, la division sont effacés par les ressacs, les reflets d’une vague, insufflant le rythme au monde.Ce rythme engendre des suites infinies de glissements, projections, de fondus enchaînés où s’abandonne la différence des genres, où les règnes s’accouplent pour faire naître des corps en suspens, des sujets réels, travaillés sans cesse par le virtuel des mythologies ou des sciences-fictions. Ils sont des blocs de pierre tout autant que des fantômes, des nageurs, comme des noyés. Ils parlent vrai tout en chuchotant qu’ils ne sont qu’acteurs et artifices. Un de leurs états est semblable à celui des objets abandonnés, « aux restes », qui deviennent espaces sacrés, idéalisés, auréolés par des énigmes faisant de notre perception une quête initiatique.

Ici, les corps peuvent être soumis par la réification pour, dans l’instant suivant, la faire voler en éclat grâce à la puissance d’une pensée onirique. Ici les héros sont aussi les dormeurs, ou ceux pour qui le sommeil est une leçon. Dormir, aujourd’hui, est héroïque. Bien heureux ceux qui, pour connaître le monde, choisissent d’en être les dormeurs actifs.

« Mourir, dormir, rêver peut-être », écrit William Shakespeare au cœur du monologue d’Hamlet, qui par cette formule livre son secret. Cette trilogie, ces trois actes indissociables ne forment qu’un principe, un seul état, une seule pensée cherchant à se libérer et à s’offrir les chances d’imaginer un nouveau monde. Un monde où s’observe le travail d’abolition entre l’humain, le végétal et l’animal. Georges Bataille serait heureux de voir qu’il s’incarne dans la présence et les déambulations d’une panthère noire, vecteur de la connaissance grâce à une mystérieuse dépense d’énergie, une course vive. la transparence traverse cet univers, à la manière de Sebastiano Mazzoni, de Francis Picabia ou de François rouan. le végétal envahit l’architectural, puis l’animal, pour se fondre enfin en anatomies humaines irriguées par les humeurs, les liquides, l’eau qui composent nos larmes, rappelant notre nature fluide et volatile, entre mémoire et épanchement. Si une part de la vie est recelée dans nos os, comme l’imagine Edgar Poe ou l’artiste roy adzak, ces os ne pèsent pas, n’immobilisent pas car ils sécrètent les rêves, véritables acteurs des bouleversements qui nous déterminent. Sont-ils l’identité la plus fiable de notre corps, comme le proposent ces œuvres, dont l’une s’origine dans le thème philosophique et poétique du « change » d’Orlando de Virginia Woolf, alors que d’autres mettent en scène la « forme monstre » ou les corps électriques de lovecraft.

Quel est le réel de ces corps ? Celui d’un paradoxe où le plus physique, le plus matériel se manifeste par le virtuel le plus insaisissable. Celui des Ailes du désir de Wim Wenders ou celui de t.S. Eliot cherchant à formuler son désir d’incarner l’écriture par une parole improférée, une parole silencieuse. Un des artistes de Panorama 23 note : « J’aimerais pouvoir dire, tenter le silence dans la parole. » l’écriture peut être une maison qui quitte ses assises, se retourne en barque pour suivre son chemin vers la mer, par la rivière, vers les figures du rêve.

Une maison ? Une barque ? Singulières « anima » ? Je me souviens, aujourd’hui, d’une question posée à un danseur derviche, évoquant sans cesse l’âme : « Mais qu’est-ce que l’âme ? » Je me souviens mieux encore, en 2021, à tourcoing, de sa réponse : « Mais le corps bien entendu !

Olivier Kaeppelin