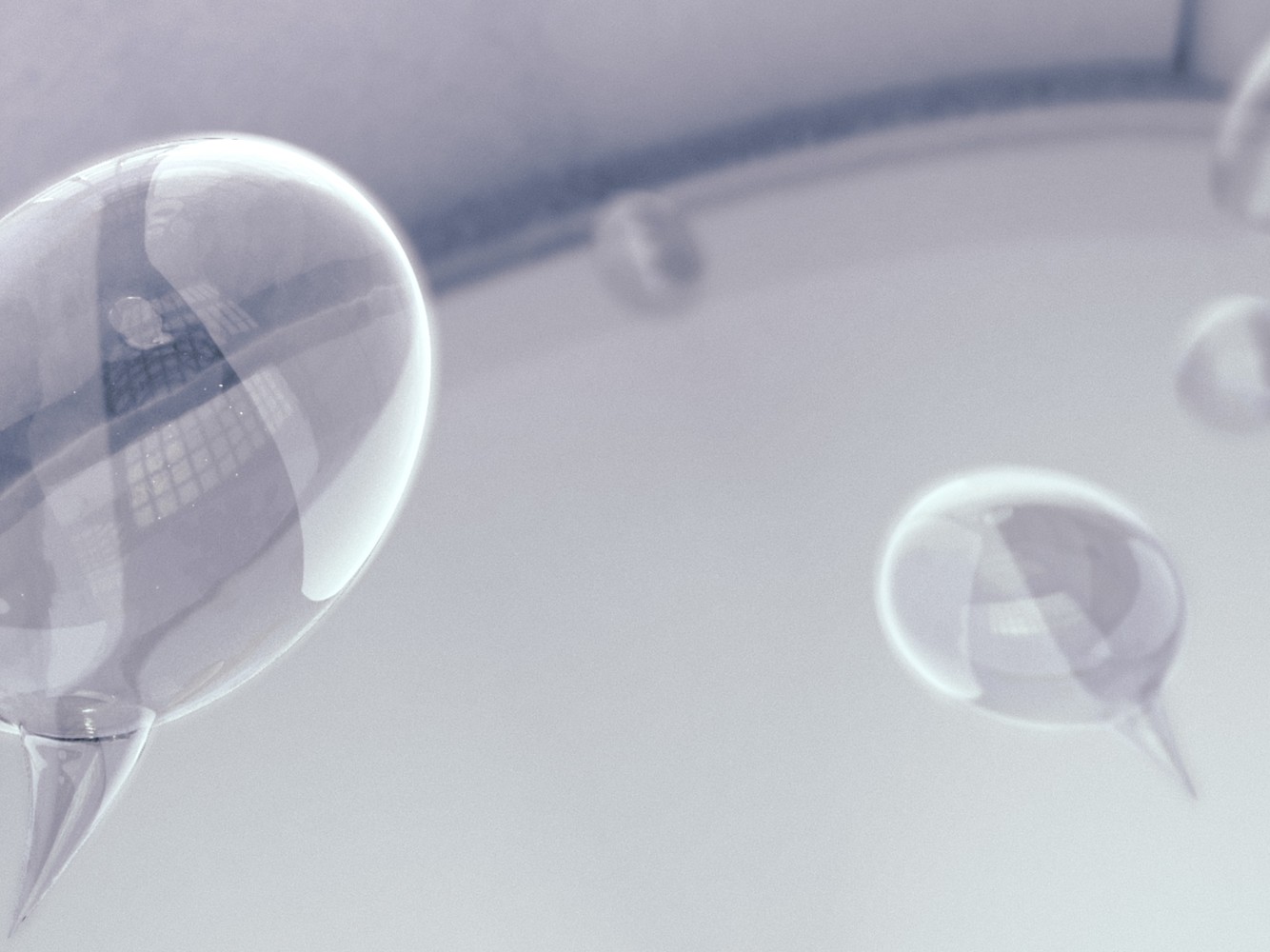

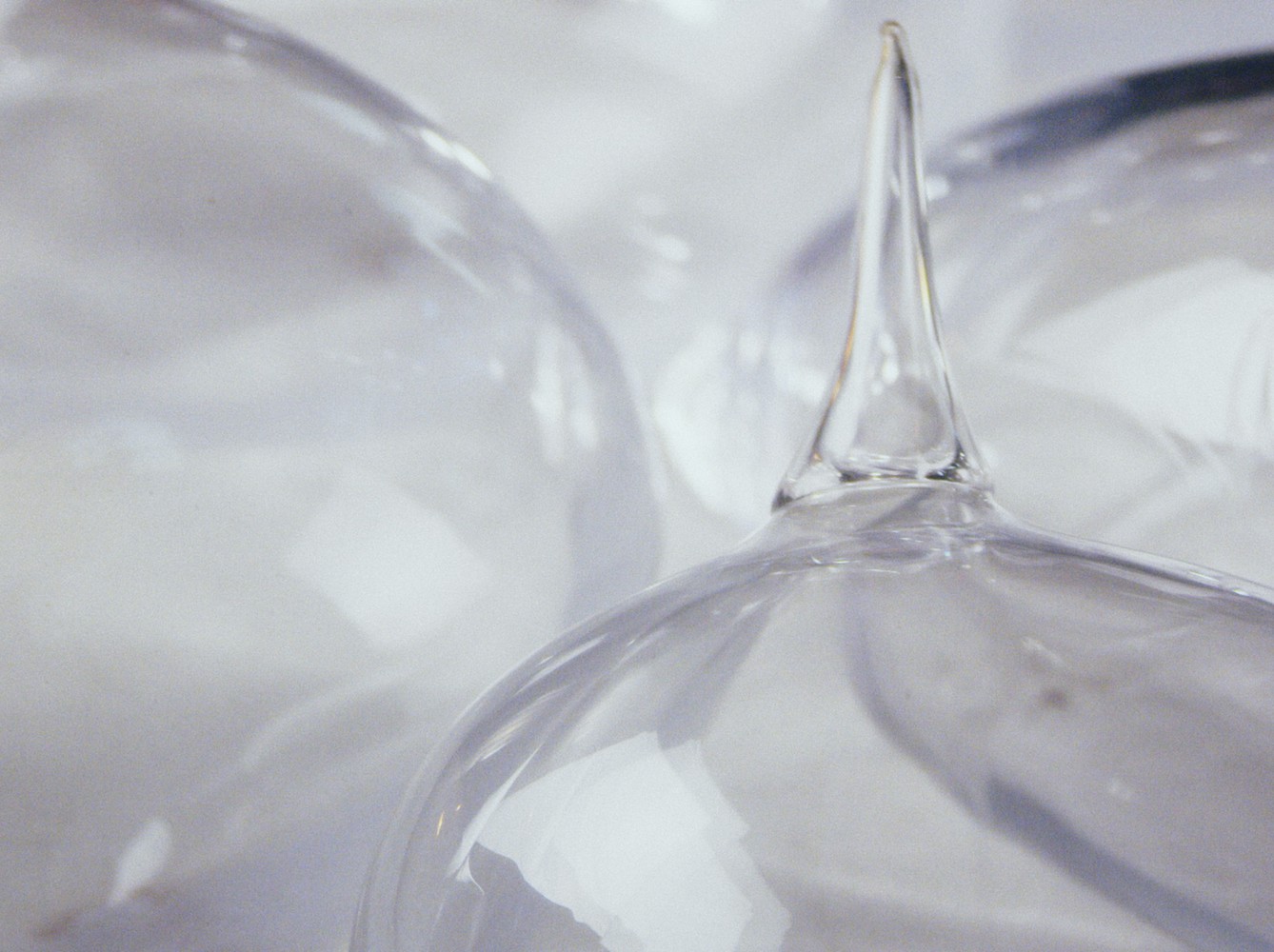

Le langage est une matière organique visible. Détachée de tout émetteur, cette substance a la particularité d’être transparente et celle de pouvoir être traversée. La matière langage se déploie dans son propre milieu et à sa propre échelle, dans un va-et-vient entre différents états : celui d’un magma ou celui de cristallisations aux formes solides et creuses. Au cours du processus, la matière fluide laisse échapper une prosodie. Celle-ci cherche constamment à se manifester, à s’extraire et à se définir. Il s’agit d’ausculter cette tentative de formulation. Pour faire l’expérience tangible du langage, il faut aussi employer une intelligence artificielle qui utilise les paramètres de la voix parlée ou chantée, générant une prosodie à partir d’enregistrements vocaux. L’inexprimable de la langue fait ici résonner les potentiels plastiques – du sonore et du visuel – comme un mouvement performatif qui traverse l’objet filmique.

Merci à Jérôme Nika et Elliot Eugénie.

Camille Zisswiller et Nicolas Lefebvre forment un duo d’artistes. Entre image fixe et vidéo, leur travail explore les moyens par lesquels les individus investissent des environnements réels ou fictifs. Favorisant les glissements entre plusieurs supports, leur recherche résulte d’un dialogue élargi qui conduit à approcher les images par surprise dans l’intervalle entre l’écriture et ce qui est formulé au-delà du langage. Chacun de leurs projets prend place dans un milieu spécifique ; des territoires en marge où les images apparaissent en secret, comme des chroniques vernaculaires. Diplômé·e de l’École du Louvre (Paris), de l’université de Strasbourg, puis de la HEAR (Strasbourg) et de la Cambre (Bruxelles) ; effectuent ensemble un post-diplôme au Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains et participent à des résidences de création à Pékin (Xu Yuan Center), Venise (Biennale d’architecture), Nijni Novgorod (Vyksa AIR), Saint-Jans-Cappel (Villa Marguerite Yourcenar).

Nos vies nous mettent en face de l’autre, de son visage et de son corps. Cette expérience induit un espace auquel, tous les deux, nous apparte-nons. Celui du cosmos, de l’énergie que nous échangeons. Cette énergie est une pure dépense, un « abouchement » avec le monde.

Elle permet de pénétrer un univers qui ne se réduit pas à ce que l’on voit, à ce que l’on touche. Nous le connaissons par les effets de sa substance comme à travers les hypothèses qu’ils permettent.

La matière est là, investie par le virtuel qui la détermine, au point par-fois d’occuper toute la place, nous livrant aux vertiges des jeux et des métamorphoses. S’agit-il d’un pur insaisissable, désincarné, concept décliné en grappes d’idées ou en structures systémiques ? Non, car s’emparant de ces hypothèses, le rêve nous détrompe. Il est un passeur, pour une exploration « suspendue » d’espace en espace. L’emploi des mots peut éloigner l’incarnation mais n’oublions pas Icare et sa double nature entre ascension et gravité. Cette ambivalence nous conduit au sein des territoires de l’art. Ils sont l’équivalent du tableau de Brueghel l’ancien1, de celui de Daniel Pommereulle l’in-terprétant, ou de la poesis, comme le rappelle Yves Bonnefoy dans ses Entretiens 2 cités par un article à leur sujet3. Pour Yves Bonnefoy, la poésie [fait] « apparaître et vivre un lieu et un moment ». Cette apparition n’est pas aisée : « On a beau espérer délivrer les mots de leurs contenus conceptuels qui réduisent le monde à des figures abstraites et incomplètes, on restera toujours en deça de ce que Rimbaud nommait la vraie vie. »

Pour les créateurs, tout l’enjeu est là, car aujourd’hui le réel se présente sous forme de banques d’images, d’archives, de data, de processus de décryptage et d’encodage. Le réel s’élabore par des suites de suppositions et de compositions. Les problématiques d’un programme, d’un dessein, d’une symbolique débattent avec l’autogénération d’une forme « en soi ». Les figures de cette contradiction se lisent dans les ins-tallations, les scénarios, les performances, les films : figures d’une présence impalpable. Celles de ce « feu follet » qu’évoque Vladimir Jankélévitch : « Qu’on ne nous reproche donc pas la nature insai-sissable de ce feu follet puisque nous en faisons profession ! Nous professons ce dénuement. Notre science dénuée nous prive de tout point fixe, de tout système de référence, de contenus facilement déchiffrables ou délégables qui nous permettraient d’épiloguer, d’ali-menter le discours et d’ouvrir un long avenir de réflexion. Notre science nesciente est plutôt une visée, un horizon, elle a donc fait son deuil de la consistance substantielle en général. »

L’emploi d’une visée, la recherche d’un horizon, nous les vivons avec Panorama 23. En son centre, un pas de deux entre « le lieu et le moment » et un principe de déplacement, généré par un mouvement ayant fait le deuil d’une consistance substantielle. Ce pas de deux fertile dénote cet insaisissable par les volutes d’une « peau ».

De quoi est faite cette « peau » ? Disons, donc cette « étoffe » qui n’est pas le résultat d’un tissage d’idées. Est-ce un tapis volant ?

Il est fait d’espaces assemblés, de cartes, qui sont autant d’écrans qu’un instant je retiens.

Nous y suivons des embarcations semblables au Pequod d’Herman Melville, à des engins dans l’air, des véhicules de pensée ou des nuages qui filent.

Que nous offrent-ils ? Des frontières dépassées, des points aveugles et des renversements, en un mot, les dimensions mentales de l’uni-vers. Le futur infiltre le passé par effraction.

Notre environnement est un planétarium et nos phrases, nos images se multiplient dans d’étonnants kaléidoscopes.

Les œuvres du Fresnoy sont les formidables accélérateurs de nos circumnavigations au sein de la nature du monde. Elles appellent la liberté de ressentir et de penser.

Cette phrase d’Emanuele Coccia, pour son film, est une porte d’entrée idéale sur ces travaux : « Pour s’orienter dans ce ciel couché au sein de tout objet, il faut construire des cartes astrales à la manière des anciens. Apprendre à lire la matière comme on lit le ciel » ou, plus loin, « le ciel est la chair de tout ce qui existe. »

Ainsi une œuvre, grâce à l’intelligence artificielle, explore dans des textes sacrés l’intensité et la violence qui s’attachent au mot Dieu. D’autres pointent du doigt le « peu de réalité » de nos lexiques et syntaxes, de leurs interrelations sans objet, prolongements contemporains de la mécanique du Procès, des machineries de Kafka.

Une autre encore nous entraîne vers le nord, où le jour et la nuit se confondent sans fin, à partir d’une cartographie, d’un terri-toire reconstitué, interdit d’ap-proche sensible mais rétabli par les archives. Pure construction mentale, elle nous livre à la magie des ruines. Celle de bâtiments militaires, imaginés pour des stratégies de contre-espionnage, de défense, du « monde libre ». Sic transit gloria mundi. Ils ne sont plus que rêves d’une toute puissance oubliée, déplacés sur d’autres théâtres d’opérations.

Au détour des parcours, un « cube » minimal nous offre de jouer avec la vie de bactéries, en milieu clos, sublimée par une surface projetée. Invisible et fascinant écosystème à l’intérieur des corps.

Sur une autre scène, grâce à une technologie post-digitale, les objets s’évaporent et changent de substance. Employant toutes les res-sources contemporaines de l’image et du son, nos mots se cristal-lisent, le langage devenant transparent à lui-même. Nous le traversons et, dans l’espace soutenu par des lignes de chœurs, il est rythme volatile, fluidifiant la matrice linguistique.

Le réel, ici, est bien ce « tissu » tantôt diaphane, tantôt fantôme, promesse d’un ciel retourné, enterré, trésor au sein d’un champ où peuvent disparaître nos cinq sens, comme dans ce film où les vaisseaux spatiaux s’abîment en un fond océanique, ultra-abyssal, inaccessible. L’auteure de ce film4 propose cette phrase qui qualifie la poétique de ces travaux présents dans Panorama 23 : « Il s’agit d’observer le monde tel qu’il ne nous apparaît pas et d’inventer la possibilité de le redécouvrir. » Ou de le découvrir… encore…

Grâce à l’art, plus vivant que la nature elle-même, cette « peau insaisis-sable », ce voile sont une provocation au rêve qui les déchire, les outre-passe. Il ne s’agit pas de traverser les miroirs mais d’aller vers « l’autre » ; mais, cette fois, un autre sans visage et ne cessant d’apparaître, un « autre » entre l’obscur de la grotte et les lumières du ciel. L’autre vérité, n’est-ce pas le véritable nom de l’art ? L’art ne dit pas ce qui va arriver, il est un espace, sans début, sans fin, sans haut ni bas pour Orphée, mais, cette fois, pour un Orphée qui aurait le droit de se retourner.

Olivier Kaeppelin