Synopsis : Le personnage principal, Ewa, est une jeune femme qui entame une carrière de médecin. Elle suit une formation dans un centre de simulation à l’allure futuriste, où elle affine ses compétences en participant à des simulations très réalistes, en incarnant un mannequin de cire médical et en se livrant à des jeux de rôle. À un moment, elle commence à ne plus faire la distinction entre expérience et simulation. Souffrant d’insomnie et de paranoïa, elle est confrontée à une situation où elle doit trouver le moyen de différencier la réalité de la fiction.

Concept : La nécropolitique (A. Mbembe) et le biopolitique (M. Foucault, P. Preciado) décrivent des systèmes de pouvoir où la société se voit bridée par le contrôle des aspects biologiques des vies individuelles. Lorsque le corps devient politique, il ne représente plus l’intimité ni l’autonomie, mais se transforme en espace d’oppression exposé. Réduire une personne à un corps privé d’intimité et de capacité est un acte d’une rare violence. Le stress et la paranoïa causés par le fait de vivre dans un tel environnement deviennent le décor de Growing, qui se déploie entre la réalité et sa réception profonde et subjective par le protagoniste. L’action du film se déroule dans un centre de simulation médicale, l’une des unités d’enseignement pratique des soins de santé actuellement en place. Les centres de simulation ne diffèrent pas d’un véritable hôpital – le seul élément artificiel y est le corps humain. Les futurs soignants s’entraînent sur des mannequins et des accessoires automatisés qui remplacent les patients humains en faisant sans cesse les mêmes gestes : respirer, saigner – et accoucher. Dans les films d’horreur, comme Alien (1979) et Prometheus (2012), réalisés par Ridley Scott, la grossesse porte les mêmes traces : elle est inattendue, incompréhensible et impossible à supprimer. À mesure qu’il croît dans le corps humain, le sentiment d’horreur augmente. Il est troublant de constater à quel point la réalité individuelle peut se rapprocher de la fiction, en prenant pour exemple la loi anti-avortement récemment imposée en Pologne, qui oblige les femmes enceintes à accoucher à n’importe quel prix, indépendamment de leur volonté et de leurs capacités. Growing recourt au motif de la grossesse et au genre cinématographique du body horror (horreur corporelle). À l’instar de Répulsion, de Polanski, l’expérience du personnage prend une tournure psychosomatique et suspendue entre la peur, la folie et le réel, car elle n’est plus à même de distinguer la simulation de l’expérience réelle. La peur et la paranoïa d'Ewa grandissent – littéralement – en elle. Pourtant, Ewa diffère des protagonistes féminins de Polanski. Contrairement à Rosemary’s Baby (1968), elle refuse ce qui naît de la peur inséminatrice, de la réalité oppressante – et, comme Médée, elle le tue. Son acte ne fait pas forcément signe vers une fin positive. La violence étant la seule réponse qu’autorise la réalité du film, imaginaire ou réelle, même s’il semble libérateur, l’acte d’Ewa appartient, malgré tout, à la réalité violente qui l’a engendré.

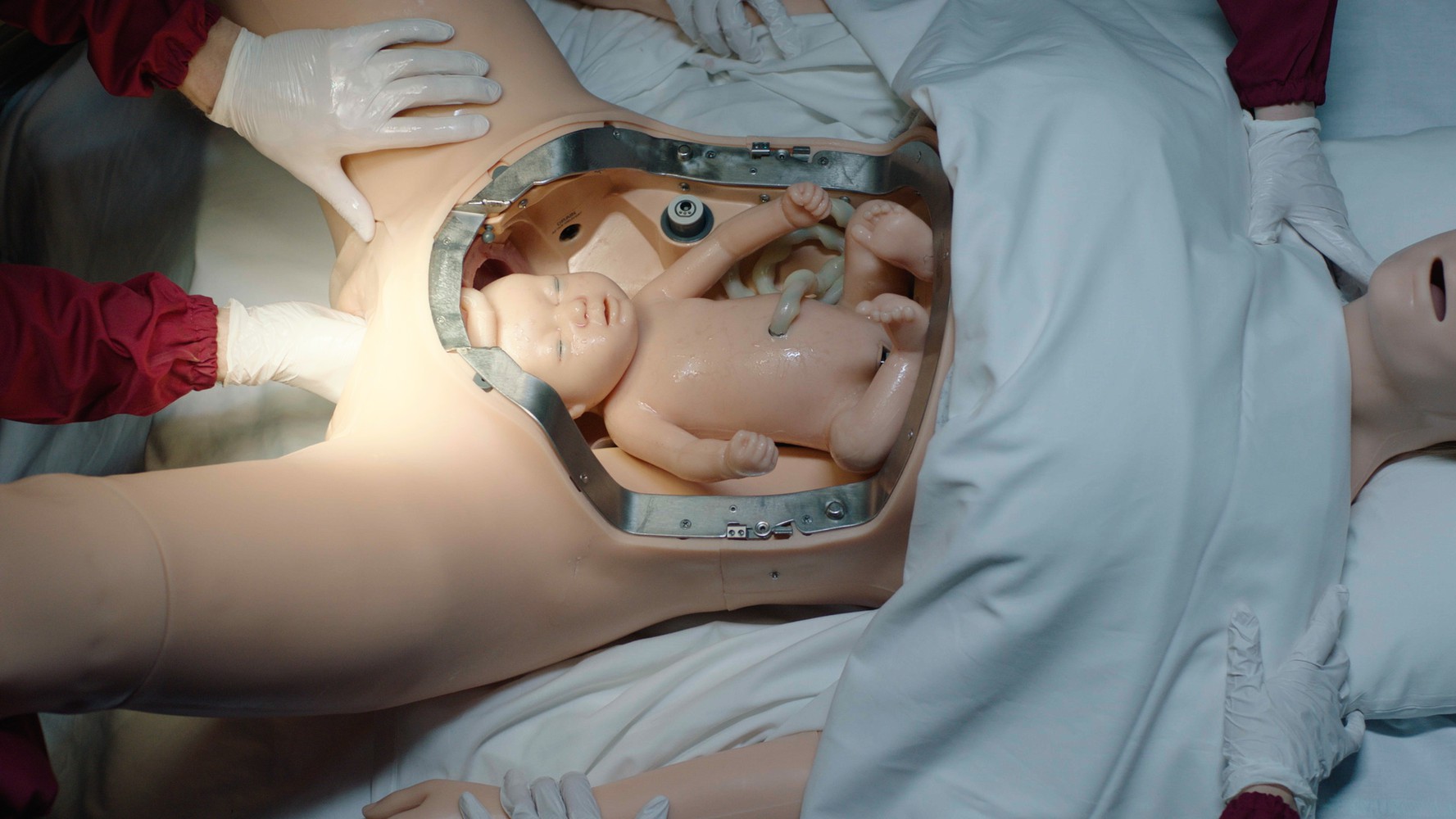

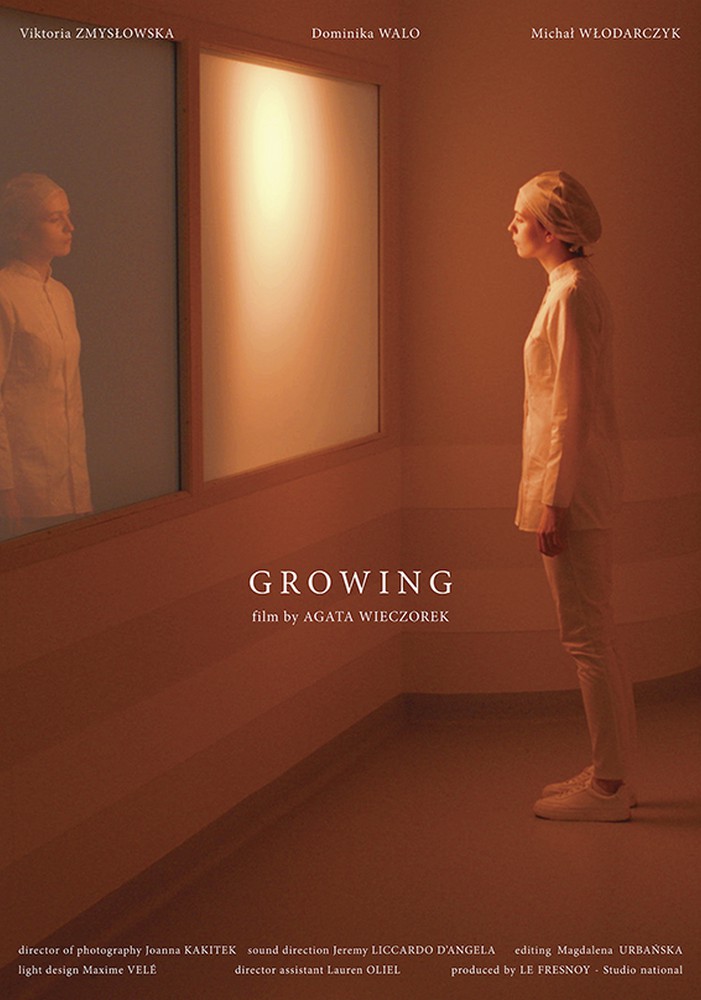

En 2020, l’artiste polonaise, Agata Wieczorek entreprend une série de photos & vidéos intitulée Growing. Actuellement en résidence au Fresnoy - Studio national des arts contemporains, elle réalise la partie filmique. Chargée de production du projet, Estelle Benazet Heugenhauser, également autrice, nous raconte le film et sa portée : « dans un espace chirurgical, des soignants s’affairent autour d’un mannequin aux jambes écartées, posées sur des étriers. Des mains s’accordent, décollent le ventre comme le couvercle d’un coffre, et au milieu de la structure de plastique et de métal, apparait un petit humanoïde prêt à naître. D’autres mains, du côté de la vulve en silicone cherchent à extraire le petit corps, un mécanisme à piston s’active et le met au monde. [...] Avec les mannequins high-tech, nous apprenons en simulant les soins. Nos diagnostics s’automatisent, nous devenons des cyborgs, et avec cette méthode de pointe utilisée par les sciences appliquées, la création de savoir se produit comme n’importe quelle autre opération machinique. Après la scène d’accouchement des humanoïdes, Ewa la protagoniste, étudiante en médecine fait face au petit : la bouche enfantine remue comme pour exprimer quelque chose, mais il s’agit simplement d’une réaction pneumatique de l’être de silicone. [...] Ewa est enceinte à son tour mais refuse sa grossesse. La médecin la félicite et s’abstient d’énoncer le choix possible de l’avortement. Ewa rentre chez elle. Plus tard, dans son appartement, du sang coule le long de ses jambes. Ewa accouche seule. Sur le sol où se sont répandues les caillots de chair, Ewa découvre cet être abject et luisant qu’elle a mis au monde. Elle s’empare d’un couteau et le hache. Ancienne étudiante de l’École Nationale de cinéma de Lodz, où a également étudié Polanski, (Répulsion, Rosemary’s baby), Wieczorek est de fait l’héritière d’un patrimoine cinématographique de l’horreur. [...] La brutalité des images est la seule réponse possible à la violence subit par toutes ces femmes, à qui la mécanique sociale et culturelle impose un destin de mère. C’est aussi une façon de nous alerter quant au contexte politique polonais actuel, où le droit à l’avortement a été supprimé en octobre dernier. Rappelons que 42% des femmes dans le monde n’ont toujours pas accès à ce droit humain.

Remerciements particuliers au Centre de Simulation en Santé PRESAGE (Plateforme de recherche et d’enseignement par la simulation pour l’apprentissage des attitudes et des gestes), un département de la faculté de médecine Henri-Warembourg (Université de Lille), pour nous avoir aimablement accordé l'accès à leurs locaux pour le tournage du film.

La pratique d'Agata Wieczorek combine le film et la photographie tout en évoluant entre le documentaire construit et la fiction documentée. Le corps humain, placé dans des situations à la fois extrêmement intimes et extrêmement politiques, est un sujet récurrent dans ses oeuvres, qui examinent les économies de genre et la marchandisation du queer, les politiques identitaires et la manière dont elles sont employées par les stratégies du pouvoir gouvernemental. Elle est actuellement artiste au Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains (2020-2022). Elle est diplômée de l’École nationale du film de Lodz, en Pologne (direction de la photographie), et de l’académie des arts Strzeminski de Lodz, où elle a étudié la peinture et l’impression d’art.

Cursus2017 -- 2020

The National Film School in Lodz, PL

Direction of Photography and TV Production Department

Master Degree with Distinction

Major: Photography

Second cycle program (2 years)

2011 -- 2016

The Strzeminski Academy of Fine Arts, Lodz, PL Graphics & Painting Department

Master Degree with Distinction

Major: Multimedia

Long cycle Master program (5 years)

Production : Le Fresnoy, Studio national des arts contemporains

Nos vies nous mettent en face de l’autre, de son visage et de son corps. Cette expérience induit un espace auquel, tous les deux, nous apparte-nons. Celui du cosmos, de l’énergie que nous échangeons. Cette énergie est une pure dépense, un « abouchement » avec le monde.

Elle permet de pénétrer un univers qui ne se réduit pas à ce que l’on voit, à ce que l’on touche. Nous le connaissons par les effets de sa substance comme à travers les hypothèses qu’ils permettent.

La matière est là, investie par le virtuel qui la détermine, au point par-fois d’occuper toute la place, nous livrant aux vertiges des jeux et des métamorphoses. S’agit-il d’un pur insaisissable, désincarné, concept décliné en grappes d’idées ou en structures systémiques ? Non, car s’emparant de ces hypothèses, le rêve nous détrompe. Il est un passeur, pour une exploration « suspendue » d’espace en espace. L’emploi des mots peut éloigner l’incarnation mais n’oublions pas Icare et sa double nature entre ascension et gravité. Cette ambivalence nous conduit au sein des territoires de l’art. Ils sont l’équivalent du tableau de Brueghel l’ancien1, de celui de Daniel Pommereulle l’in-terprétant, ou de la poesis, comme le rappelle Yves Bonnefoy dans ses Entretiens 2 cités par un article à leur sujet3. Pour Yves Bonnefoy, la poésie [fait] « apparaître et vivre un lieu et un moment ». Cette apparition n’est pas aisée : « On a beau espérer délivrer les mots de leurs contenus conceptuels qui réduisent le monde à des figures abstraites et incomplètes, on restera toujours en deça de ce que Rimbaud nommait la vraie vie. »

Pour les créateurs, tout l’enjeu est là, car aujourd’hui le réel se présente sous forme de banques d’images, d’archives, de data, de processus de décryptage et d’encodage. Le réel s’élabore par des suites de suppositions et de compositions. Les problématiques d’un programme, d’un dessein, d’une symbolique débattent avec l’autogénération d’une forme « en soi ». Les figures de cette contradiction se lisent dans les ins-tallations, les scénarios, les performances, les films : figures d’une présence impalpable. Celles de ce « feu follet » qu’évoque Vladimir Jankélévitch : « Qu’on ne nous reproche donc pas la nature insai-sissable de ce feu follet puisque nous en faisons profession ! Nous professons ce dénuement. Notre science dénuée nous prive de tout point fixe, de tout système de référence, de contenus facilement déchiffrables ou délégables qui nous permettraient d’épiloguer, d’ali-menter le discours et d’ouvrir un long avenir de réflexion. Notre science nesciente est plutôt une visée, un horizon, elle a donc fait son deuil de la consistance substantielle en général. »

L’emploi d’une visée, la recherche d’un horizon, nous les vivons avec Panorama 23. En son centre, un pas de deux entre « le lieu et le moment » et un principe de déplacement, généré par un mouvement ayant fait le deuil d’une consistance substantielle. Ce pas de deux fertile dénote cet insaisissable par les volutes d’une « peau ».

De quoi est faite cette « peau » ? Disons, donc cette « étoffe » qui n’est pas le résultat d’un tissage d’idées. Est-ce un tapis volant ?

Il est fait d’espaces assemblés, de cartes, qui sont autant d’écrans qu’un instant je retiens.

Nous y suivons des embarcations semblables au Pequod d’Herman Melville, à des engins dans l’air, des véhicules de pensée ou des nuages qui filent.

Que nous offrent-ils ? Des frontières dépassées, des points aveugles et des renversements, en un mot, les dimensions mentales de l’uni-vers. Le futur infiltre le passé par effraction.

Notre environnement est un planétarium et nos phrases, nos images se multiplient dans d’étonnants kaléidoscopes.

Les œuvres du Fresnoy sont les formidables accélérateurs de nos circumnavigations au sein de la nature du monde. Elles appellent la liberté de ressentir et de penser.

Cette phrase d’Emanuele Coccia, pour son film, est une porte d’entrée idéale sur ces travaux : « Pour s’orienter dans ce ciel couché au sein de tout objet, il faut construire des cartes astrales à la manière des anciens. Apprendre à lire la matière comme on lit le ciel » ou, plus loin, « le ciel est la chair de tout ce qui existe. »

Ainsi une œuvre, grâce à l’intelligence artificielle, explore dans des textes sacrés l’intensité et la violence qui s’attachent au mot Dieu. D’autres pointent du doigt le « peu de réalité » de nos lexiques et syntaxes, de leurs interrelations sans objet, prolongements contemporains de la mécanique du Procès, des machineries de Kafka.

Une autre encore nous entraîne vers le nord, où le jour et la nuit se confondent sans fin, à partir d’une cartographie, d’un terri-toire reconstitué, interdit d’ap-proche sensible mais rétabli par les archives. Pure construction mentale, elle nous livre à la magie des ruines. Celle de bâtiments militaires, imaginés pour des stratégies de contre-espionnage, de défense, du « monde libre ». Sic transit gloria mundi. Ils ne sont plus que rêves d’une toute puissance oubliée, déplacés sur d’autres théâtres d’opérations.

Au détour des parcours, un « cube » minimal nous offre de jouer avec la vie de bactéries, en milieu clos, sublimée par une surface projetée. Invisible et fascinant écosystème à l’intérieur des corps.

Sur une autre scène, grâce à une technologie post-digitale, les objets s’évaporent et changent de substance. Employant toutes les res-sources contemporaines de l’image et du son, nos mots se cristal-lisent, le langage devenant transparent à lui-même. Nous le traversons et, dans l’espace soutenu par des lignes de chœurs, il est rythme volatile, fluidifiant la matrice linguistique.

Le réel, ici, est bien ce « tissu » tantôt diaphane, tantôt fantôme, promesse d’un ciel retourné, enterré, trésor au sein d’un champ où peuvent disparaître nos cinq sens, comme dans ce film où les vaisseaux spatiaux s’abîment en un fond océanique, ultra-abyssal, inaccessible. L’auteure de ce film4 propose cette phrase qui qualifie la poétique de ces travaux présents dans Panorama 23 : « Il s’agit d’observer le monde tel qu’il ne nous apparaît pas et d’inventer la possibilité de le redécouvrir. » Ou de le découvrir… encore…

Grâce à l’art, plus vivant que la nature elle-même, cette « peau insaisis-sable », ce voile sont une provocation au rêve qui les déchire, les outre-passe. Il ne s’agit pas de traverser les miroirs mais d’aller vers « l’autre » ; mais, cette fois, un autre sans visage et ne cessant d’apparaître, un « autre » entre l’obscur de la grotte et les lumières du ciel. L’autre vérité, n’est-ce pas le véritable nom de l’art ? L’art ne dit pas ce qui va arriver, il est un espace, sans début, sans fin, sans haut ni bas pour Orphée, mais, cette fois, pour un Orphée qui aurait le droit de se retourner.

Olivier Kaeppelin