Installation : sculpture de matelas en mousse, vidéo sur écran de télévision, chaises, rideaux en plastique.

Installation : sculpture de matelas en mousse, vidéo sur écran de télévision, chaises, rideaux en plastique.

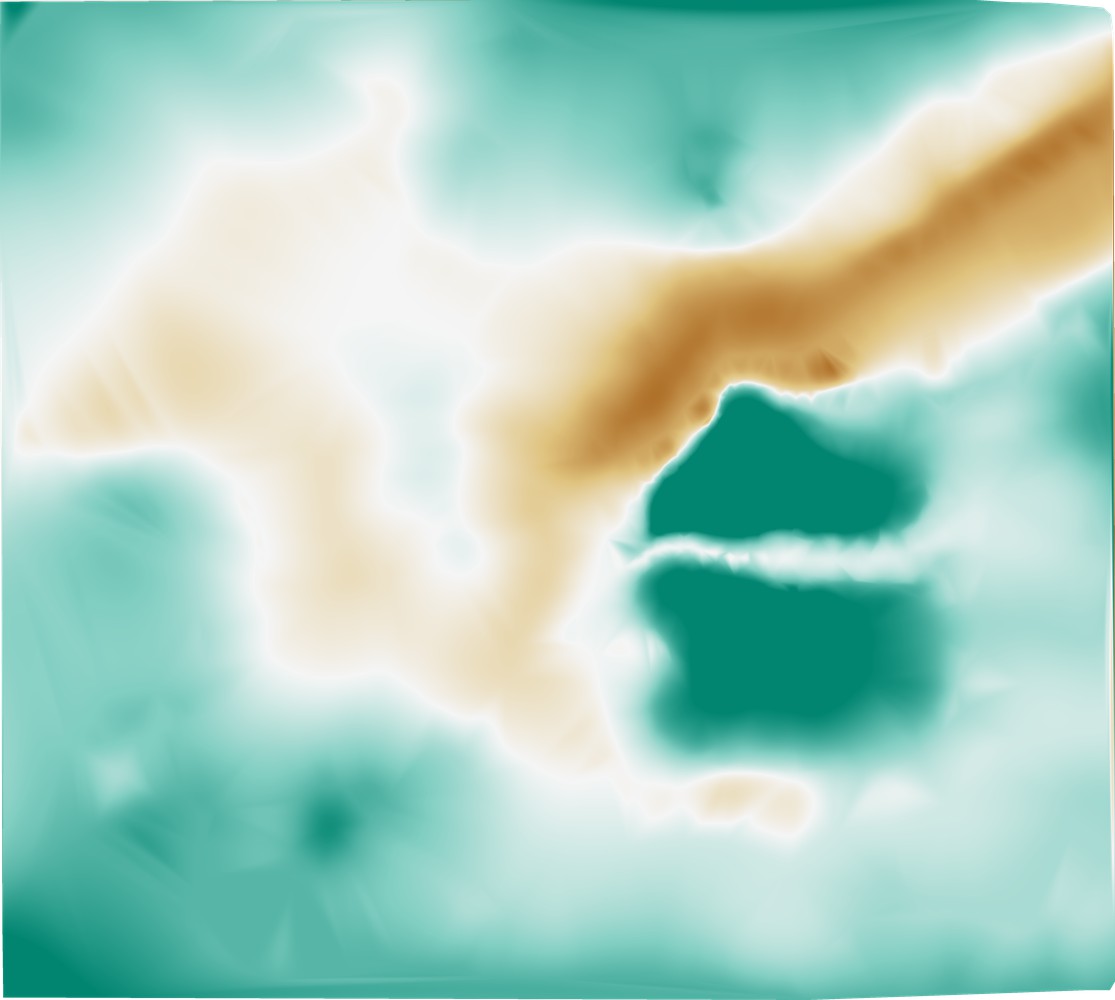

The Woman Next Door est une installation qui exprime la poésie de l’espace domestique en tant que mémorial pour ceux qui sont morts (seuls). Le centre de cette installation consiste en une sculpture-matelas. Le matelas incarne le cycle de la vie : on y naît, on y meurt. Il est en soi un espace de vie privée et d’intimité où faire l’amour, dormir, pleurer, rêver. De loin, la sculpture-matelas ressemble à un lit normal, nu et blanc. Pourtant, à la regarder dans le détail, le visiteur se rend compte que sa surface est anormale, marquée de contours, de reliefs et de formes qui peuvent évoquer un paysage de montagne et de fleuve, mais aussi – parce qu’il s’agit d’un matelas – l’image rémanente d’un corps humain imprimé sur le lit : déformation, décomposition, absence. Les empreintes sur la surface du matelas sont le fruit de la transformation d’une photographie de famille endommagée ayant appartenu à une vieille dame décédée. Le processus de transformation commence par le travail d’un géologue qui crée une carte imaginaire à partir de la photographie avant de convertir la carte en matelas. Dans la superficie ténue d’un lit double de 135 cm x 191 cm, on se met pourtant à rêver à travers le corps de l’autre.

Nicolas Graux, Thomas Schira, Guangli Liu.

Quý Trương Minh est né à Buon Ma Thuot, petite ville située dans les hauts plateaux du centre du Vietnam. Ses récits et ses images, situés entre le documentaire et la fiction, le personnel et l’impersonnel, s'inspirent du paysage de son pays natal, de ses souvenirs d’enfance et de l’histoire du Vietnam. Ses films ont été montrés dans des expositions et des festivals internationaux tels que Locarno, New York, Berlin, CPH:DOX, la Viennale, Clermont-Ferrand, Oberhausen, Rotterdam et Busan. Il a remporté le premier prix artistique de la 20e édition de VideoBrasil, à São Paulo, en 2017. Il expérimente aujourd’hui des idées et médias nouveaux au Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains.

Michel Dubois et Éric Armynot du Chatelet, géologues à l’université de Lille, campus Cité scientifique, département des Sciences de la Terre, laboratoire de génie civil et géo-environnement (LGCgE), Laurence Landon, décoratrice, Huimin Wu, graphiste.

Production : Le Fresnoy, Studio national des arts contemporains

L’âme et le corps, les frontières, les fractures entre matériel et immatériel, les jeux qui proposent de les abolir... Ici le réel et le virtuel sont ensemble sur un fil funambule. l’empiriste David Hume écrivait : « tous les matériaux de la pensée sont tirés de vos sens, externes et internes, c’est seulement leur mélange et leur composition qui dépendent de l’esprit et de la volonté 1. » Dans Panorama 23, il ne s’agit donc pas du choix d’un idéalisme exalté ou d’un goût prononcé pour une magie des illusions, mais bien plutôt d’une réponse à la réalité du monde par l’expérience. la question est alors d’étayer notre pouvoir créateur sur ce qui nous permet de concevoir cette réponse, sans négliger aucune de ses dimensions, en particulier celle du rêve. Celle-ci ne se contente pas de l’accomplissement physique du vol pourtant si proche des légendes oniriques. Ce signe ascendant, cette élévation, que nous permettent-ils ?

Un avion, un planeur, présents dans une des œuvres, ne sont plus les assemblages d’Icare ou de simples mécaniques, mais des véhicules mentaux, des traductions, d’une nature à l’autre, qui en disent beaucoup sur nos capacités de vivre « ailleurs », au-dessus d’une ligne d’horizon, qui « éclairent » autrement les connexions des synapses de nos vies cérébrales.

Cette énergie transformatrice nous projette au-delà. Débordant l’écosystème entre le ciel et la terre, elle génère la conscience d’un corps, désormais parcelle vivante du cosmos. Ce corps cosmique est solidement attaché aux jours et aux heures de nos vies, entraîné en une déambulation permanente au sein de l’espace, composé des territoires instables de la mémoire et des forces lancées vers je ne sais quelle rive. Si nous ne les maîtrisons pas, c’est parce que nous sommes entre leurs chorégraphies les liant et les déliant. nous appartenons à l’histoire de nos corps mais nous la dépassons sans cesse pour des univers que nous cherchons à habiter ou dans lesquels nous nous projetons sur des écrans visibles ou invisibles. Dans ces films, des êtres humains naissent ou s’éteignent. J’entends à peine leur souffle. leurs yeux sont fermés... ils dorment. Sont-ils plongés au fond d’eux-mêmes, fascinés par les teintes humorales, les circulations sanguines, les secrétions qu’ils sont, en secret, les seuls à voir, comme autant de spectateurs solitaires ? Contemplent-ils leur nature abstraite, leurs territoires internes, leurs ballets colorés, leurs multiplications ou leurs disparitions.

Il faut lâcher, alors, les codes de la réalité pour le réel et ses multiples manifestations à l’écart des lexiques. le corps n’est plus devant nous. Il s’est transformé en une poignée d’obscur, une terra incognita, ou l’arbre, le Tree of life de terence Malick dont nous supposons les lignes qu’il trace, depuis l’entrelacs de ses racines jusqu’au bleu du ciel. Étrange généalogie dont le personnage central est la naissance.

Il y a dans Panorama 23, un rêve qui s’épanouit à partir des inductions de la nature. Elles sont à la fois les acteurs, leurs songes et les scènes qui les accueillent. l’important est, alors, qu’entre les lignes, chaque lapsus, chaque vide, chaque absence, chaque tempête, chaque éclipse, relance le rythme. l’essentiel est la confiance en une continuelle genèse que la musique accompagne, ostinato, spirale sonore qui, s’abandonnant à son propre mouvement, gagne tout l’espace pour nous offrir un lent émerveillement. l’éclosion d’une fleur, d’une écriture, d’une création magnifie cet espace grâce à la surprise et à la beauté de leur croissance. Croissance fascinante du rose, d’une pleine couleur, rose de l’aurore, celui de la chair, rose de Goethe, celui de Guston, ou de Gertrude Stein, « a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose... »

Ce désir, ce plaisir, cette jouissance offrent à notre corps la chance d’être plus grand que soi, animé par le sentiment océanique ou l’infini d’un ciel sans bords, d’un sommet, d’une couleur, sans attribut. Cette couleur peut être le bleu du ciel, de Georges Bataille, de Franck Venaille, le blanc du cosmos ou encore le vert secret d’un brin d’herbe, infime dans l’univers. Ce secret, les artistes nous invitent à le découvrir. Le secret comme source d’émotion et de pensée. Est-il caché dans le tapis, circule-t-il dans les écheveaux de Panorama, le labyrinthe des œuvres ? C’est lui qui donne sa puissance à la création, comme le souligne anne Dufourmantelle : « C’est une force motrice dont on explique mal la créativité. Ses liens avec la mémoire et le langage, notamment dans son rapport au rêve, sont l’objet d’enquêtes et d’expériences qui nous conduisent à repenser l’imagination. (...) le secret qui se révèle dans l’imaginaire n’est jamais une mise à sac ou un arrachement, c’est un monde de lumière et d’ombres où l’on se déplace comme un animal 2, à l’instinct (...) le secret reste le trait qui lie efficacement la vie du désir et la possibilité qu’offre le réel de le recevoir. on suppose donc au réel d’être révélateur d’un désir auquel il offre une possibilité de fixation et de répétition. En reliant divers moments de notre vie, de jour comme de nuit, la vie secrète de nos désirs confère son visage à notre plaisir. n’est-elle pas cette fixation hors parole d’une image ?

Comment dès lors la dévoiler sans mettre en périls, le fragile édifice d’arrêt sur image et donc d’arrêt du temps sur lequel il repose. »les installations, les films de Panorama la dévoilent, en « reliant les divers moments de notre vie de jour comme de nuit ». Ils sont à la recherche d’une image et, dans le même temps, la bouscule, la défont, s’en libèrent pour toucher du doigt une matière non grammaticale et d’autant plus mobile. Je la perçois mais je ne peux la traduire. Plutôt que de la chercher à travers les énoncés, je m’attarde sur les blancs du discours, ses points aveugles, ses effacements, en vérité, une fois de plus, sur son énonciation dont le rythme heurté en dit plus que l’illusion d’une narration. C’est pourquoi dans ce Panorama, les technologies les plus avancées font signe aux techniques rudimentaires, « primaires » ou vernaculaires de l’art brut. C’est là, je crois, que se tient la preuve de la puissance créative du secret. Il nous empêche de dire et permet ainsi de créer en empruntant des chemins de traverse.

À ce sujet, anne Dufourmantelle écrit : « Ce qui fait son pouvoir est aussi d’être au-delà du bien et du mal. Se construisant au tout début du bien et du mal. Se construisant au tout début de notre rapport au langage, il n’est pas étranger à la conscience morale mais il la déborde. Il impose en nous sa valeur d’atout, c’est-à-dire ce qu’il troque, ce qu’il augmente au contact du réel et se déploie dans les interstices du manque, de la frustration, de l’attente, dans les délices du rêve, du premier toucher, des premières sensations, des premières visions.

»Éclipses, égarements, disions-nous, mais aussi présence d’un espace-temps intercalé entre deux mondes, d’un corps hybride, ou encore d’un corps s’échappant comme le corps de loup. Dans ces territoires « écartés », chacun est confronté au vide, aux désordres du vent qui renversent, aux mirages et aux chants des sirènes de l’Odyssée. Plus que sur des routes, ou des parcours balisés, nous sommes « au milieu du carrefour », à la recherche de « ce qui vient ». En art, l’essentiel n’est jamais le programme mais l’archipel des expériences, le pressentiment ou la conscience d’un choix. Certaines œuvres nous rassurent en nous donnant la certitude de « voir », avant que d’éprouver que ce qui est proche s’éloigne, que le sens se voile. la vue qui ainsi s’élève ne saisit plus le motif, se trouble, s’aveugle volontairement, pour retrouver le réel « autrement », non plus en une saisie directe mais dans les dédales du secret que l’on cherche. Désormais, il ne s’agit plus de vue mais de la libération d’une énergie mentale se détachant de l’objet pour mettre en œuvre une approche, polymorphe et sensuelle.

Dès lors, l’art nous permet de « toucher » le cœur, la peau du réel, sachant que l’un et l’autre s’évanouiront dans la nuit des images, où, entre ciel et terre, nous partons, tâtonnant, à leur recherche : le cœur, la peau...

Olivier Kaeppelin