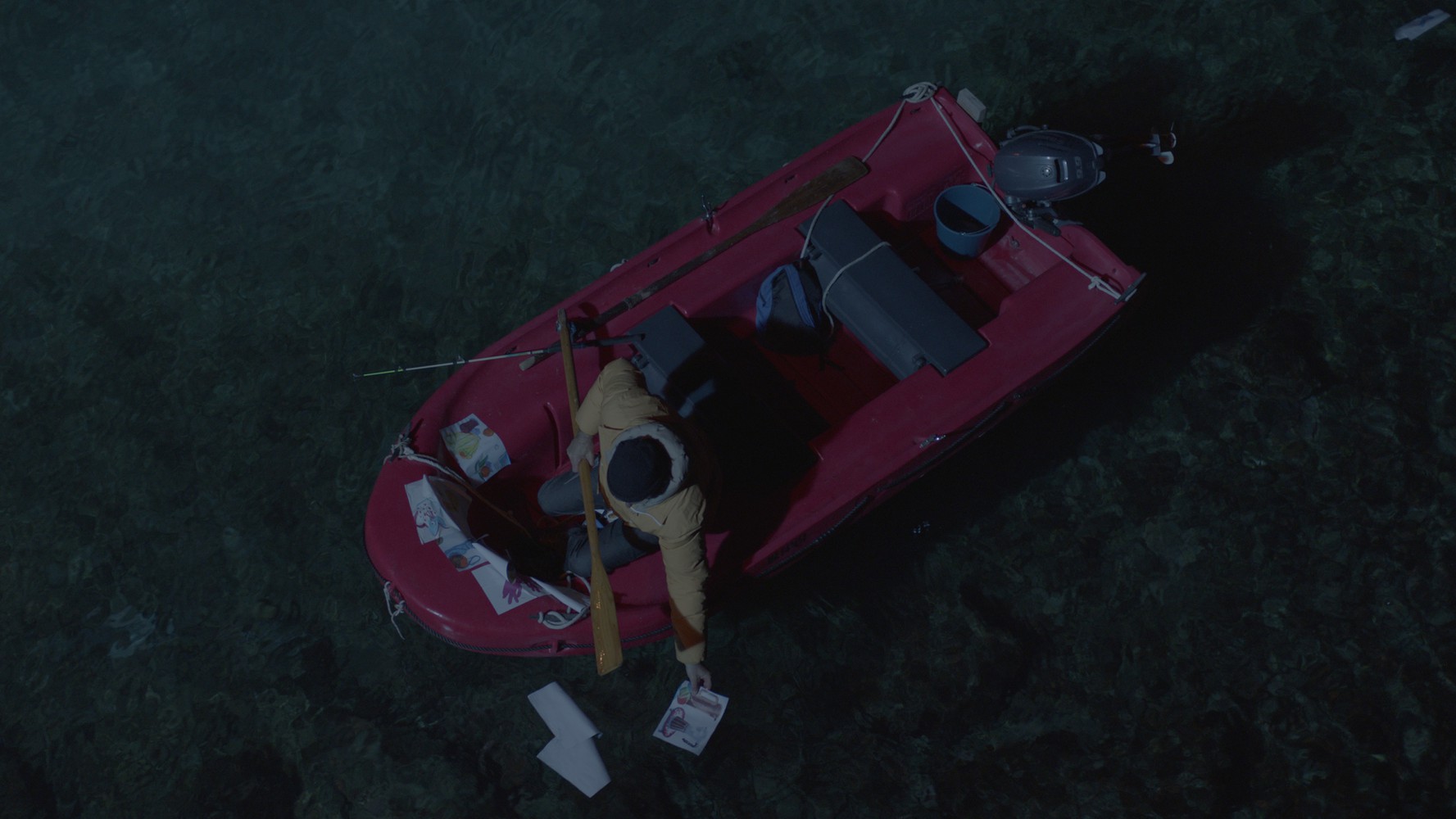

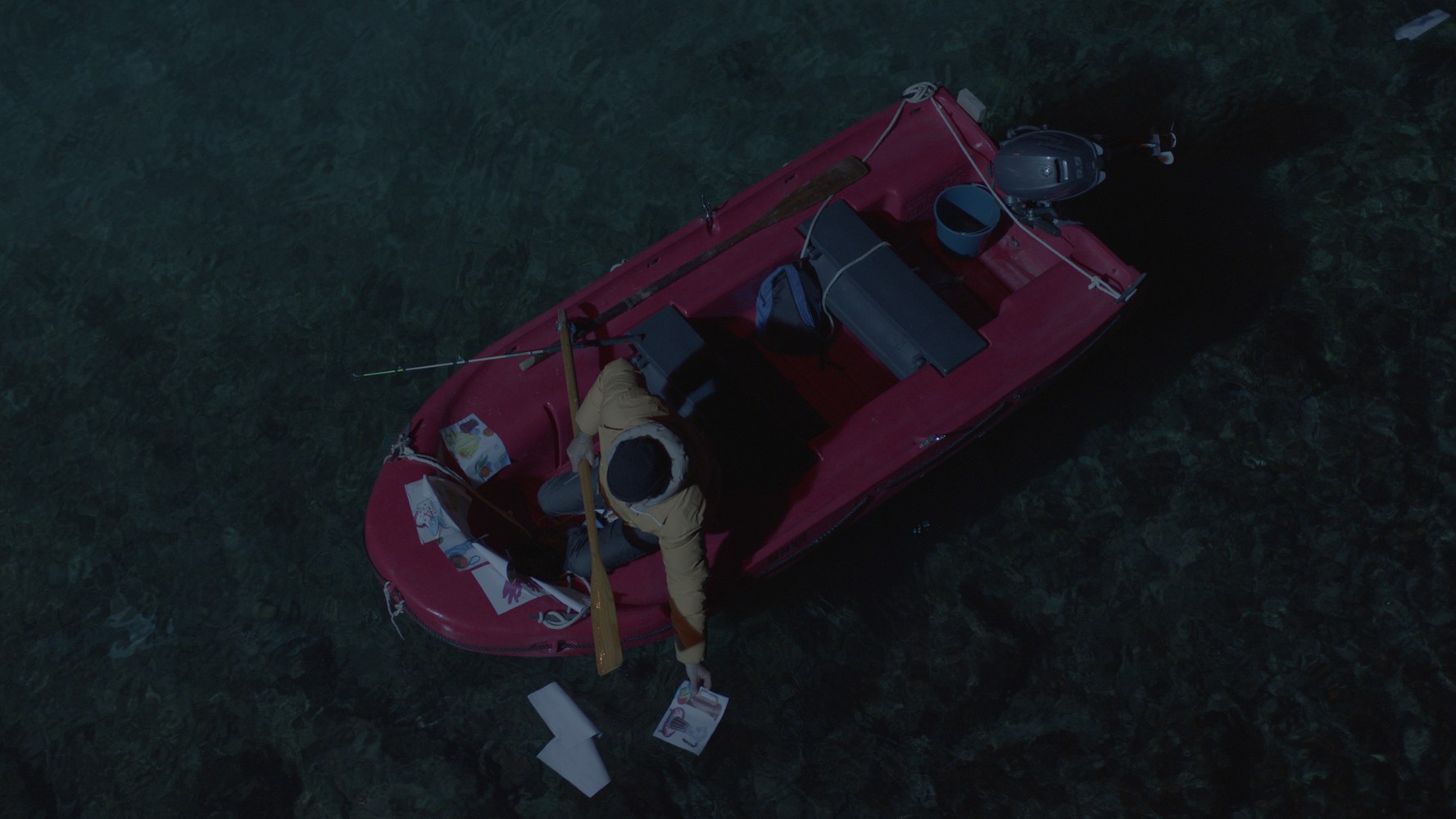

Au principe de ce film seraient les objets, leur propension à mener une vie autonome et à engendrer une narration multiple et labyrinthique. Progressivement, ces objets se voient adjoindre des gestes : saisir, caresser, frotter, lancer, casser, vendre, voler, jouer… De ces usages naissent des situations et des personnages qui tissent un récit-palimpseste où le fil des images s’enchevêtre comme dans une tapisserie ou le tapis dans lequel – pourquoi pas – on se prend les pieds car les objets se font indices et fausses pistes, dans une dynamique ludique. Le décor est à l’échelle de la ville de Marseille. La cité dont le pouls s’emballe est habitée par un mouvement continu, sans contrôle, qui dépasse toujours les limites. Sur la temporalité d’une journée, les objets déploient leurs usages couplés à l’action des divers personnages : un homme de ménage pêcheur, une artiste peintre de vanités, de charmants voyous, un vieux couple d’amants sado-maso, une jeune femme en rouge aux bas noirs rayés de blanc ou encore le roi des antiquaires. Le quotidien glisse progressivement vers l’absurde, et le récit devient objeu, pour reprendre le terme de Francis Ponge. Ainsi a lieu la rencontre explosive entre une brosse raide et un portefeuille poilu, une cafetière boit la tasse, une orange pleure sans que l’on sache l’objet de son chagrin, des gants respirent avant une bonne matinée de ménage, une corde après avoir levé l’ancre lie des amants, à l’arrachée un sac est volé, une bouée souhaite connaître la vie terrestre, partout les dessins volent et les dés sont lancés…

Marie, Laurent, Louise, Lou, Daniel, Joachim, AMP Métropole

Née à Marseille en 1997, Lou Le Forban entre aux Beaux-Arts de Paris en 2015. Elle passe un an en échange à la Kunstakademie de Düsseldorf. En 2020, elle obtient son DNSAP et commence à étudier au Fresnoy. Elle est membre de deux collectifs artistiques centrés sur la performance et le commissariat d’exposition, Triovisible et Sheesh collective. Sa pratique est faite de va-et-vient entre le dessin, la danse et la vidéo.

Ma première surprise est de remarquer que la majorité des travaux de Panorama 23 ne présente pas de discours politiques alors qu’aujourd’hui, les rhétoriques idéologiques reviennent en force.

Après ce premier étonnement, je suis heureux d’observer que cela ne dénote pas un désintérêt pour la société ou les tragédies de la pla-nète : immigrations, dictatures, catastrophes écologiques, massacres, violences machistes, pour ne citer que les plus récurrentes, mais que les créateurs, ici, choisissent des réponses proprement artistiques.

Si ma première réaction est la surprise, la deuxième est le bonheur de voir que ces créateurs ne désertent pas leur territoire, leur langage propre. Ils interpellent, analysent, inventent en rappelant que leur mode d’expression, leur méthode, engendrent d’autres attitudes, d’autres com-positions, d’autres formulations du sens.

Découvrant cela, m’est revenu en mémoire la radicalité de Jeanne-Claude et Christo, avec lequel j’ai présenté, à la Fondation Maeght, le travail de toute une vie sur la forme archétypique du Mastaba, à par-tir de l’utilisation de formes industrielles telles les boites de conserve, les bidons ou les barils. À la vue de ces barils, nombre d’interlocuteurs tinrent des considérations sur le pétrole, l’économie, l’écologie concernant cette éner-gie fossile. Si Christo laissait, bien sûr, les journalistes libres de leur interprétation, il indiquait que ce n’était pas le sujet de son travail et qu’ayant connu cruellement, en Bulgarie, le pouvoir destructeur de l’idéologie, il ne souhaitait pas s’entretenir sur son œuvre de cette problématique. Sans vouloir offenser personne, si son questionneur insistait sur ce thème, il interrompait l’échange, en leur demandant de comprendre sa défiance vis-à-vis de ce mode de pensée qui, selon lui, étouffait l’espace singulier de l’art et de son processus signifiant.

Je crois, en effet, qu’un artiste n’a aucun intérêt à se laisser envahir, coloniser par ces démarches réductrices. S’il y a une « éthique générale », il y a également une éthique de l’art qui détermine son champ propre.

Je me souviens qu’un journaliste lui demanda alors : « mais pour quoi militez-vous ? ». Christo répondit en souriant : « Mais comme toujours, je milite pour l’art, simplement ». Christo signifiait qu’avec les formes qu’il inventait, qu’il choisissait, il construisait « un effet d’art », c’est-à-dire une « rencontre » avec un événement artistique. Il ajoutait, un peu provocateur : « Je crée des œuvres complètement irra-tionnelles, irresponsables, sans justification. » Ainsi, à chacun d’entrer en un contact très libre, très singulier avec l’univers pour le comprendre autrement. Que ce soit la nature, la ville, les enve-loppes sociales ou intimes… cette rencontre se fait grâce à l’art qui use de ses propres géographies et de ses propres chemins. Ce sentiment, je l’éprouve aujourd’hui en regardant ou en vivant les œuvres de Panorama qui, claire-ment, disent leur désaccord avec certaines structures sociales, leurs fonctionnements, leurs insuffisances, leurs injustices, leurs erreurs ou absurdités, mais qui, jamais, ne rendent leurs armes au politique ou à une autorité en matière de sciences sociales. Cela n’implique pas une absence de dialogue mais souligne qu’ils n’ont pas la même économie, ni le même imaginaire. Ce n’est pas un hasard si le souvenir de cette expérience avec Christo refait jour, aujourd’hui, tant j’ai retrouvé au Fresnoy des options comparables.

Je suis heureux de voir la société en débat de cette façon et la place que les artistes s’y assignent, choisissant délibérément que leur langage soit irréductible à d’autres, empêchant ainsi la confusion entre la réalité et le réel.

Là encore, un autre souvenir : celui de Jean-Luc Godard, au Verger Urbain V d’Avignon, en 1967, après la projection de La Chinoise. Assailli de questions d’actualité ou de théo-ries politiques, de demandes d’analyses, il explique qu’il est cinéaste, qu’il faut d’abord regarder le film, l’assemblage des images, de la parole et du son, pour comprendre son propos. Le sens était là et ne pouvait pas être réduit à aucun argumentaire, aucune rhétorique.

Là encore, ces phrases de Léos Carax dans un entretien avec Jean-Michel Frodon : « Jamais aucune idée au départ de mes projets, aucune inten-tion. Mais deux trois images, plus deux trois sentiments. Si je découvre des correspondances entre ces images et ces sentiments, je les monte ensemble. (…) Je ne fais pas de films ouvertement politiques, mais je crois toujours que le cinéma existe pour nous changer, et changer nos angles de vision ».

Christo, Jean-Luc Godard, Leos Carax, autant de manière de dire que l’art, le cinéma, la poésie, ont chacun leur espace, leur régime propre où se cherchent la singularité et l’autonomie de leurs « langues ». Les idées, les sensations, les raisons y ont un autre poids, un autre dessin, une autre forme. C’est ce choix que ne cesse de faire vivre les œuvres de Panorama lorsqu’elles mêlent leurs voix à celles de l’époque et du temps.

S’il s’agit, par exemple, d’expri-mer la douleur générée par le racisme, au travail à bas bruit, la fiction s’en empare, redonne vie à la Vénus hottentote, à son corps morcelé. Elle renverse l’aliénation extrême de ses pauvres membres pour, désormais, les faire rayonner, d’un merveilleux « rose » à travers le moindre de ces fragments dépecés. Ils deviennent formes sacrées dressant un sanctuaire, les préservant de manipulations dont ils furent et dont ils sont encore l’objet.

Devant la confusion des sentiments, les stéréotypes d’époque, la soumission à l’ordre des techniques, les artistes ont recours aux pouvoirs de la surprise, de l’enfance, aux rêves et aux voiles de l’ima-ginaire qui se gonflent et invitent nos vies, de manières inattendues, parfois « tordues », à déjouer l’ordre et les règles, à faire entendre l’humour et l’ironie qui défont les lignes droites, nous obligeant à être « le suivant d’un suivant. »

« Au suivant ! » dirait Jacques Brel. Pigeons. Crânes d’œuf après crânes d’œuf. Ils sont aussi de véritables détona-teurs contre certains personnages de la scène #MeToo. Semblables au Pantalone de la commedia dell’arte, ils sont présents depuis l’Antiquité jusqu’aux grotesques de la Renaissance. Ils ont les traits parfois sans pitié de l’art brut ou portent les grimaces des morphings numériques de Joan Fontcuberta. Leurs corps se déforment, sous l’effet des jouissances du pouvoir et de celles du corps de l’autre.

Beaucoup de jeux de rôles nous interpellent, de scène en scène. Certaines violences s’inspirent des mises en scène, des games de combat parodiant des biographies d’assassins devenus des producteurs de cinéma de série B, remplaçant les duels de valeureux samouraïs.

D’une fiction à l’autre, beaucoup de personnages surgissent et sont traités, non plus pour leurs corps, mais comme des « composi-tions-combinaisons » abstraites, au sein d’allégories ou d’expériences vécues ou rejouées dans le théâtre des installations.

Il arrive aussi que, quel que soit le masque ou la peau du rôle, les person-nages, malgré de volontaires distanciations, ne puissent être soustraits aux émotions mémorielles souvent mélancoliques ou dramatiques, « Persona – Personne – Personnage » se mêlant.

Dora García évoque la déception de femmes toujours dans l’espérance d’un monde à venir qui ne vient pas, l’impossible recon-naissance authentique de leur identité. Le monde se repliant sur lui-même n’offre plus alors que la répétition désespérante des mêmes échappatoires. « Sortir du champ » est alors une aventure dont la force motrice est le rêve.

EXIT, sortir, s’extraire, voilà ce que les peuples de migrants incarnent. Ces peuples qui traversent les terres vers la mer. Ils franchissent les déserts, réparent leurs sandales, pour continuer à marcher, abandonnent leurs bagages, leurs vêtements puis leur vie... Ils ne laissent rien, si ce n’est, grâce à quelques-uns respectant leurs rêves, une tombe sans nom, dans l’espoir qu’un jour une famille, une communauté les reconnaîtront. Qu’en est-il, aujourd’hui, de ces fantômes et des possibilités d’îles imaginaires à atteindre ? Une chanson dit que ce refuge est toujours vivant pour ceux qui les suivent et chantent à nouveau.

La plupart de ces œuvres n’ont pas de narrations formelles mais des élaborations « complexes » inattendues qui nous maintiennent en éveil, à la recherche d’une issue virtuelle au labyrinthe. Je pense à John Cassavetes qui confie à propos de Love Streams : « Faire un film n’a rien à voir avec les actions, la narration, la conti-nuité, mais comment on reste accroché au sujet. À chaque fois que quelqu’un pense qu’il va se passer quelque chose, dans ce film, il se passe autre chose. Bon, ça aurait pu avoir un meilleur plan narratif, mais on fait un film et on se dit : ça pourrait être mon dernier film. Pourquoi j’irais me mettre dans un plan narratif vous comprenez ? Et puis on claque juste après, vous voyez. »

C’est alors que la pensée onirique prend son envol. Elle nous projette dans un journal intime ou une légende, en nous offrant la perspective heureuse de se diriger vers « l’Ailleurs ».

Rien n’est affirmé, ni stable. L’art, la musique, l’amitié, la vie autonome des objets concourent à négliger la seule dimension matérielle de nos vies. Ce que je vois est dépassé par une « autre vue », une connais-sance nouvelle des genres et des règnes. La nature nous incite à faire un pari sur la présence de l’invisible, sur le principe d’incertitude. Le monde est une supposition, potentiellement vérifiable, ce dont, régulièrement, la physique quantique nous informe.

De cette liberté efficiente, le refus d’un système autoritaire de perception et d’interprétation est le garant. Il n’affronte pas le politique, il le contourne, le désamorce. L’hypothèse est clai-rement de choisir l’Ailleurs, comme analyseur de notre situation. Ici, les œuvres cherchent à l’atteindre en mixant le rêve, la science, l’uto-pie, les déplacements de la pensée, le mouve-ment, paradoxalement, plus concret que toute fondation.

Imaginons une ville. Ce n’est pas son bâti qui la fait vivre, car la ville est une étoffe brodée d’habitants, d’arbres, de temps, de mémoire, de cir-culations et de frémissements. Son réseau est un réseau sanguin. Il fait et défait sans cesse la carte. Épiderme rêvant une fiction entre science et animisme.

Olivier Kaeppelin